Your Guide to What’s Happening in New Hampshire’s Lakes Region

Gilmanton's Beginnings

By Kathi Caldwell-Hopper

Picture this idyllic New England scene: old, well-kept, whitewashed homes. Stately elm trees bursting with fall foliage or summer’s greenery on streets and scenic backroads. All this and much more describes rural Gilmanton, NH, a town that has known a long and fascinating history.

Yesteryear

Gilmanton's Beginnings

By Kathi Caldwell-Hopper

Picture this idyllic New England scene: old, well-kept, whitewashed homes. Stately elm trees bursting with fall foliage or summer’s greenery on streets and scenic backroads. All this and much more describes rural Gilmanton, NH, a town that has known a long and fascinating history.

Whether a blessing or a curse, most people know Gilmanton as the setting for Grace Metalious’ widely read novel “Peyton Place”. Tourists find it odd that this tranquil village so steeped in history was said to be the setting that gave Metalious the inspiration for Peyton Place, a book which reached best-seller status.

The town that was to become Gilmanton was incorporated in 1727; Colonial Governor John Wentworth signed a charter on May 20.

At that time, the Lakes Region as a whole was unsettled country, full of wild animals, thick forests and sometimes unfriendly (and who can blame them, given the track record of some white settlers to live peacefully with the native people) Native Americans. Still, as with all land in the new country, men were eager to stake a claim and reach for a better life.

In the case of Gilmanton, the land was granted as pay for 24 members of the Gilman family and 153 other men who fought in defense of the colonies.

The conditions of the charter were: proprietors must build 70 dwelling houses and house a family in each within three years of charter. Also, they must clear three acres of ground for planting; each proprietor must pay his portion of town charges; a meetinghouse must be built for religious worship within four years. The members had to build a house for a minister and another for a school. All these conditions were to be met, if the peace with the Indians lasted the first three years of settlement.

If any settler defaulted on those conditions, he would lose his share of land.

As to why the town was named Gilmanton, the name Gilman appears time and time again in early records, and the family, originally from Exeter (indeed, most of the proprietors were from the seacoast/Exeter area), had fought valiantly during war times.

Because of the fear of Indian attacks, the original conditions were not met, and it wasn’t until 1749 and 1750 that settlers came to town to pick out lots and work the land. Even then, these men did not stay long for many reasons.

Over and over again, through the years to follow, the settling of Gilmanton was a stop and start affair, due largely to the dangers of warring Indian parties. Town meetings for Gilmanton were held in the safety of Exeter, where most proprietors still lived.

If Governor Wentworth had given much thought to the land grants, he would surely have chosen a more populated area to gift land to these proprietors. While they may have fought valiantly in war times, most Exeter residents hailed originally from Massachusetts, or England. Massachusetts was already more populated, with such cities as Boston offering a taste of the fineries of life in England. The grant of land in Gilmanton may have been very unsuitable for the Exeter men.

In 1730 a committee of proprietors petitioned the Governor to allow longer time to settle the town. In 1731 Edward Gilman and others traveled to Gilmanton and marked out boundaries.

They didn’t stay long, as the French and Indian wars were about to begin. The entire Lakes Region, and Gilmanton, was a very dangerous place for English settlers to be. The French and Indian war parties used nearby Lake Winnipesaukee as a rendezvous for scouting parties, and any smoke seen at likely settlements was an easy target for attack.

By October 1748, a peace treaty was signed and the French and Indian war parties retreated to Canada. At that time, the Gilmanton proprietors could resume settlement.

Another snag in their plans happened around this time, when the deed of John Tufton Mason of Hampshire County, England (it is said New Hampshire gets its name from Mason’s home county) was brought forth. Mason held huge amounts of land in New England, and mostly in New Hampshire. He had transferred his claim of the Gilmanton area land to friends in Portsmouth. This could be a real problem for everyone, it was felt. Once again, the proprietors refused to till the land and settle in Gilmanton, when the land might not really belong to them.

The dispute was settled in 1752, and all seemed well for settlement of Gilmanton.

Once again, plans were shelved when the old French and Indian wars resumed. The wars were mostly about who owned what land. Unlike the previous war, the English decided to become aggressive to end the fighting. They staged attacks on unsuspecting French forts, and among the soldiers who fought bravely were men from Gilmanton and Exeter.

After much bloodshed, the war was finished and life could return to a sense of normalcy.

Progress in settling the new town finally took hold. By the summer of 1761, proprietors had selected, cleared and begun building on their land. Among the first to live year round in Gilmanton were the Mudgett brothers, John and Benjamin. After building houses, they brought their wives to Gilmanton.

According to “The History of Gilmanton” by Daniel Lancaster, Benjamin Mudgett and his wife Hannah traveled on snowshoes in deep snow and under very cold conditions, to arrive in Gilmanton from Epsom. They arrived at their new home on December 26, 1761, after snowshoeing a remarkable distance from Epsom in a short period of timey. Hannah was the first white female settler in Gilmanton. Soon John Mudgett arrived with his wife, and a friend, Orlando Weed followed with his wife.

Hannah Mudgett lived in Gilmanton until there were about 5,000 settlers. How different it must have seemed in comparison to her first winter in the wilderness of Gilmanton! She lived her last years with a son in Meredith and died at the remarkable age of 95. Her son Samuel was the first male child born in the Gilmanton area.

In 1762 more families arrived and by 1767, 45 families lived in Gilmanton. Soon town meetings were held there instead of in Exeter. A physician arrived in 1768 and a minister also about this time.

The town was growing, new and interesting people settled and built homes in the town. Years sped by, progress marked many areas of the town.

The town saw settlers and citizens come and go, and with them, their hopes, dreams, and their good and bad deeds.

The town that had struggled so many years to see settlement was on its way.

Back to School: the Lakes Region’s Schoolhouses

By Kathi Caldwell-Hopper

If you wish to see a real one-room schoolhouse and to experience what education was like long ago, there are many examples in New Hampshire. In the village of Andover, there were once a number of small schoolhouses, each serving a region of the town. In the 1800s, there could be many hamlets within one town, and without transportation, students could not be expected to walk miles to a distant schoolhouse, thus small buildings were erected and teachers - sometmes the local minister or his wife - stepped in to educate youngsters.

Yesteryear

Back to School: the Lakes Region’s Schoolhouses

By Kathi Caldwell-Hopper

If you wish to see a real one-room schoolhouse and to experience what education was like long ago, there are many examples in New Hampshire. In the village of Andover, there were once a number of small schoolhouses, each serving a region of the town. In the 1800s, there could be many hamlets within one town, and without transportation, students could not be expected to walk miles to a distant schoolhouse, thus small buildings were erected and teachers - sometmes the local minister or his wife - stepped in to educate youngsters.

The Tucker Mountain Schoolhouse remains in Andover to show what education was like long ago and it is open through October and run by the Andover Histosrical Society. The schoolhouse was built in 1837 and served the local community until 1893, when a fast dwindling student population led to its closing. According to information at www.andoverhistory.org, “it stands today in its original setting and location, in very good condition, looking much as it did when it was in active use.”

The schoolhouse, like most of its era, was a single room, and it measures about 16 feet by 18 feet. An “ell” or shed that serves as a weather-protective entrance to the school building was also the place for storing firewood. Another necessity was a small closet in the shed with the two-hole privy. The building is of post-and-beam construction, made of hand-hewn timbers fastened with trunnels, and it sits on a foundation of unmortared granite stones. The walls are sheathed with vertical planks, covered externally with clapboards.

Once you were at your desk, you were expected to sit quietly and in place; the pupils’ heavy plank desks were (and still are) bolted to the floor. Those who visit will see that the floor slopes downward on two sides toward the center of the room, increasing visibility for the pupils in the back rows (a frequently-seen design detail in the schools of this time). The interior walls are covered with wide pine boards painted flat black to serve as chalkboards.

The building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is now a museum exhibiting details of a way of education that no longer exists.

In the 1830s, Ashland, New Hampshire, like many New England towns, was likely a remote spot. The town was fortunate to have as a resident, Miss Nancy Perkins, as a teacher. Perkins saw the need for a school in the area, and rolled up her sleeves and started a private high school in the Vestry of the town’s Baptist church. The school was in session from 1836 to 1847, according to Ashland, New Hampshire Centennial 1868 to 1968. She was said to be a wonderful teacher and parents and students alike sang her praises. Indeed, she must have been a good teacher with a love for passing on knowledge because she eventually married Oren Cheney and together, they helped found Bates College.

Schooling was certainly different from what we experience today. In the 1880s in Ashland, grammar school students were required to take an exam written by the school board each term. Pupils had to answer 60 percent of the test questions correctly in order to advance to the next grade. Old schoolhouses – usually consisting of just one room — were a part of the American landscape for decades. Ask any older person and it’s a good bet they once attended a one-room schoolhouse. These charming little buildings were every town’s answer to education and local children from age 5 to 15 or more all sat in one room, taught by a single adult woman or man.

Conditions in many village schools were par with the rest of society’s housing at the time: a woodstove warmed the space and students were often expected to split and carry wood to feed the heat source; a bucket of water served as refreshment and another was for washing hands. Outside, usually hidden behind bushes, sat the outhouse.

A very unusual school was in session at Canterbury Shaker Village in Canterbury in the 1800s and into the 1900s. The Shaker religious sect welcomed and cared for many orphaned or foster children over the years and they were given excellent educations at the Shaker school. The one room, one-story school was erected in 1823. As the population of Canterbury Shaker Village expanded, with it came more children and in 1863 he school was expanded to become a two-story structure. Area children were allowed to attend the school as well as Shaker children.

In Sandwich, NH, the Lower Corner School was a place of learning in the mid and late 1800s. Most towns were in remote spots and many families lived in even deeper rural areas. Small schools were built to serve children in various rural locations.

The Lower Corner School began in 1825 as the John Quincy Adams School. At that time, according to information at www.sandwichhistorical.org, citizens in Sandwich voted a tax of $193.70 to build a schoolhouse. The school was small with a plank door, tiny windows that were placed high and underpinnings of stone. A big fireplace heated the building. Four-foot wood fed the fire that kept teacher and students warm during the cold winters. Fireplaces are notorious for providing uneven heat and this one, as a former student recalled, provided heat that “burned the face while the back was freezing.” Students who sat at the back of the room took turns moving to the front to share the warmth during the day.

In the 1880s the school was renamed the Lower Corner School. By the 1930s an addition brought indoor toilet and storage facilities to the school and a playground. In 1944 the school closed and students traveled to the Center School in the town.

Children in the Cook settlement in Moultonborough had a schoolhouse near a spring. The school building was modest in size; one child who attended the school was said to be the envy of all the other students because he could coast down from his home to the schoolhouse door in snowy winter weather, according to Moultonborough to the 20th Century, a publication of the Moultonborough Historical Society Bicentennial Issue 1963. As the year progressed, school children had quite a walk to get to school – down a steep hill, through fields and over stonewalls and fences. Even with the arduous walk each day, some students were said to have good or perfect attendance.

The Village School in Moultonborough was the site of learning for many years. During the early part of the 1900s the school was located opposite the Moultonboro Town House and was a one-room school. By 1913 the town improved the school as the population grew. An assistant teacher was hired in the 1920s and the school was divided and two regular teachers were hired. A jacketed stove was secured for the school and a note in town reports for 1923 stated, “The new stove makes it possible to have the rooms comfortable as far as the heat is concerned.”

In 1925 a new school had been built and housed elementary school aged children. In her book, I Remember Moultonboro New Hampshire by Frances A. Stevens, she recalled being a student at the school in the late 1920s. “As I remember, when this school was first built there was a big stove with a jacket around it in the back corner of the room. In the winter when it was real cold she would have us gather around the stove for our classes. It wasn’t long before they put in a furnace with steam radiators.”

On the other side of Lake Winnipesaukee, schooling was seen as a necessity in New Durham. The town’s original land grand specified that a portion of the community’s money be set aside for a schoolhouse. In 1779 the town raised money to hire a town school teacher and for some years after, money was voted for schooling. At this time there were no school houses in the town and school masters were hired who traveled from town to town boarding with different families. These men would teach the children of the area the basics: reading, writing and spelling.

By the 1800s schools were built in New Durham. In the late 1800s, improvements were made with the installation of blackboards, iron stoves and desks. In 1906, the annual report of the school board stated that “We cannot expect a woman to teach in a town paying $6.50 to $7.50 for 24 weeks in a year when she can obtain $8.00 to $9.00 per week for 34 to 36 weeks in the year. She will most certainly choose the latter.”

According to The History of New Durham, New Hampshire by Ellen Cloutman Jennings, the original 14 New Durham schools had shrunk to just seven with a school budget of about $1,000. Teacher’s salaries, supplies and repairs came out of this budget and the board closed schools when necessary if enrollment dropped drastically.

Further north in the Plymouth, NH area, the village of Dorchester had a small schoolhouse that was built in 1808 and originally called the North District School. It was used as a one-room school for area children until 1926. The school's last teacher was Lena Bosence Walker.

According to www.livingplaces.com, “…the 1808 Schoolhouse, a single story clapboarded structure, its gable front capped by a small gable-roofed cupola and set above a rock wall foundation.”

At excellent preserved one room schoolhouse is part of the Wolfeboro Historical Society on South Main Street. The Society owns The Clark House Museum Complex of structures at the site, including the Pleasant Valley School.

The one room school was built about 1805 on land in South Wolfeboro in the area known as Pleasant Valley according to information at www.wolfeborohistoricalsociety.org. Known for some time as District #3 School, some residents called it the Townsend School, because it was close to the home of Reverend Isaac Townsend, Wolfeboro’s first minister. (Perhaps the reverend visited the school and probably taught religious classes to the children.)

The school was crude by today’s standards, as were most in New England. Local children learned to make due. All grades were taught in the one room. The enrollment of students ranged from 20 to 50. In 1959 the schoolhouse was moved to its present location at the Clark Museum Complex. (To tour the schoolhouse museum during seasonal hours, call the Wolfeboro Historical Society at 569-4997.)

Lakes Region Airport

By Kathi Caldwell-Hopper

“The local airport, while small…still attracts the air traveler. It is not uncommon on a summer weekend to see 25 or 30 large four-place planes tied down in the parking area.” Airport News, 1958

After the 1938 Hurricane destroyed a maple syrup operation, Ralph Merwin Horn got permission from his father to replace maple syrup with airplanes. On approximately 100 acres of land at the Wolfeboro Neck property, Horn got to work clearing downed trees and doing the hard work of transforming a hurricane damaged land to an airstrip.

Lakes Region Airport

By Kathi Caldwell-Hopper

“The local airport, while small…still attracts the air traveler. It is not uncommon on a summer weekend to see 25 or 30 large four-place planes tied down in the parking area.” Airport News, 1958

After the 1938 Hurricane destroyed a maple syrup operation, Ralph Merwin Horn got permission from his father to replace maple syrup with airplanes. On approximately 100 acres of land at the Wolfeboro Neck property, Horn got to work clearing downed trees and doing the hard work of transforming a hurricane damaged land to an airstrip.

The above quote was from a 1958 Granite State News comment under “Airport News.” Many people are unaware that an airport was built in Wolfeboro in the late 1930s/1940s. It served the area and saw small planes coming and going, bringing vacationers and others to and from the Lakes Region.

Not so many years after the hurricane, World War II broke out, and Horn’s flying knowledge was put to use training military personnel to fly planes in Massachusetts.

Ralph married Eleanor and together they lived in the Wolfeboro area and worked hard to make the airport a going concern. And hard work it was to maintain a small airport that could see private planes arriving at any time of the day or evening; at first, lighting was an issue and smudge pots of fire were lit to illuminate the runway and help pilots land at the airstrip.

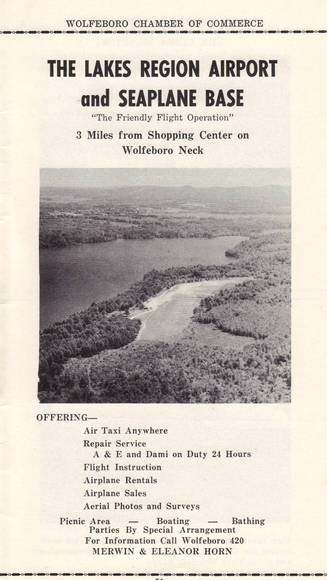

An old advertisement for the airport. (Courtesy Wolfeboro Historical Society)

A circa 1950s Wolfeboro Chamber of Commerce pamphlet promoting the business calls The Lakes Region Airport and Seaplane Base, “The Friendly Flight Operation” just three miles from Shopping Center on Wolfeboro Neck. The advertisement states that the airport offered Air Taxi Services (to anywhere); Repair Services; Airplane Rentals and Sales and Aerial Photos and Surveys.

Because of its proximity to the water, the pamphlet also states that there was a picnic area, boating and bathing, with parties offered by special arrangement.

Around 1965, the airport was said to have 1,500 ft. of unpaved runway and an adjacent seaplane base, making it a real asset to those who wanted to land via seaplane. According to “History of Wolfeboro 1770-1994” by Q. David Bowers, the Horns seaplane facility was in Winter Harbor, not far from the Lakes Region Airport. It wasn’t unusual to see, in the 1950s, a seaplane in flight. In the summer of 1955 a twin-engine “Catalina” flying boat was utilized by the Navy for seaplane practice. It took off and landed at Winter Harbor during practice, with about eight crewmen aboard.

In the winter of 1951, just about everyone in Wolfeboro was craning their necks and looking up at the sky as a flock of B-36s with jet escorts were dog-fighting over Winnipesaukee. After the display, they flew off towards Portland, Maine. The reason they were in the air above Wolfeboro? It is said the huge bombers had overflown the town on a direct air route from Texas to Europe! It can be sure the Horns were among those watching the unexpected airshow.

Business was steady and in 1974/1975, according to “History of Wolfeboro” by Bowers, the airport expanded its main runway. This was likely because more private planes were making use of the space. In addition, a year-round air taxi service by twin-engine plane was to be offered. At that time, Amphibair, Inc. offered Wolfeboro to Boston air taxi service for $26.00 per person if you had a group of five or more passengers. The service was a great idea, but clearly most who used the airport had their own plane, and the air taxi service ceased due to lack of business.

Aerial view of the airport area. (Courtesy Wolfeboro Historical Society)

The airport sought various methods to cater to the public over the years, such as a July 1983 air show sponsored by the Lion’s Club. The event featured stunt flyer Bob Weymouth, a 10 military jet aircraft, and more. Attendance was good, with about 500 people attending the air show; it also featured an antique 53-note National air calliope mounted on a show trailer!

Upkeep is always an issue for a small airstrip, but Ralph and Eleanor had some help in 1984 when 20 members of the International Organization of Women Pilots rolled up their sleeves and painted markings on the runway. It was a big help, because at that time a number of aircraft used the airport.

Even with outside help, Ralph and Eleanor were kept busy for the many years they operated the business. One remembrance on www.winnipesaukee.com recounts that there were often floatplanes at the docks, dozens of aircraft at the tie-downs, three or more aircraft in the hangar for repairs and also some in for routine maintenance, not to mention handling takeoffs and landings both day and night.

Eleanor was an active partner in the business, beside her husband from the early days of the airport. She also was a photographer of some local renown. (Indeed, an internet search under the name Eleanor Horn lists one of her aerial photos that was made into a postcard, showing Wolfeboro from the air and on the back of the card, it is printed that it was published by Gould’s Dime Store, Wolfeboro.)

When she passed away in the late 1980s, Eleanor was honored in Wolfeboro with a flyover of vintage World War II military aircraft. In 1989, scenic rides for charity in the name of the Eleanor Horn Memorial Flight to Fight Cancer was held.

Also, on www.winnipesaukee.com, a remembrance was shared from SeaBees, a water aircraft business: “After receiving gasoline from the Horns' dock, we pushed away and started the engine. The engine coughed a few times and then refused to start. The wind had allowed our craft to drift in the direction of deep water, and I had previously loaned my paddle to another pilot! With Eleanor looking on, she seemed to grasp the seriousness of the situation and did what any matronly and grandmotherly person in a print dress would do: She waded into the lake waist-deep and pulled the SeaBee back to the dock!”

The airport area was busy into the 1990s, and one former customer recalls Saturday hamburger cookouts at the airport, probably gatherings comprised of those who flew private planes in and out of the location.

Another remembers, “To me the airpark was the heart and soul of the Lakes Region.” What this meant was that, for those who used it, the Lakes Region Airport and the seaplane base offered a way to travel to and from the Wolfeboro vicinity faster than by car.

All things come to an eventual end, and the airport eventually ceased operation. Ralph Merwin Horn passed away in the 1990s, but he - and the airport - are fondly remembered by many who once took to the skies from the Lakes Region Airport.