‘Seeing Your World in Watercolor’

Larry Frates, artist-in-residence at Laconia’s Belknap Mill, has been teaching art to all ages since the 1970s, and now is venturing into new territory with a book-and-video project that aims to make the essentials of watercolor painting even more accessible.

The cover of Art To You by Larry Frates.

‘Seeing Your World in Watercolor’

By Thomas P. Caldwell

Larry Frates, artist-in-residence at Laconia’s Belknap Mill, has been teaching art to all ages since the 1970s, and now is venturing into new territory with a book-and-video project that aims to make the essentials of watercolor painting even more accessible.

The new book, Art To You With Larry: Seeing Your World In Watercolor, grew out of a collaboration between Larry, Chris Beyer, a writer and English teacher in Laconia, the Belknap Mill, and book publisher Kathy Waldron. Kathy’s company, Give a Salute, had published the book, Socks, The Belknap Mill Christmas Elf, based on the stuffed elf doll that appears in the Belknap Mill’s social media postings leading up to Christmas Eve. Beyer wrote the children’s book, using the elf to tell the history of the former textile mill-turned-museum, and Larry provided the illustrations.

Larry Frates with a display of his paintings.

Having seen Larry’s work in that book, Kathy suggested that he consider sharing his knowledge of art in a book. “I said, ‘Okay, let’s see what we can do,’” Larry recalled. “I had to sit down and sort of sift through my brain and figure out the most important parts of watercolor that I’ve been talking to my students about in class.”

Kathy encouraged him to “just start writing” and, as he did, he started looking through photographs and other images that might supplement the words. Between January and the end of May, he worked with an editor and a graphics person to pull together his thoughts and place them in a layout that communicated the joy of painting.

Larry said the name of the book came from the online classes he had been forced to do during the COVID-19 pandemic: “Art To You With Larry.”

“I couldn’t have my classes, so we had to figure out other ways of keeping the classes going — keeping the adults that I had engaged in painting,” he said.

The videos were done as a series of four classes, with Larry providing instruction and listing the materials the viewers would need to create their own paintings.

“So I started looking at that and said, ‘Well, this is something that could work with the book,’” he said.

Larry is working with photographer/videographer Alan MacRae in creating videos that will accompany the print edition of his new book. By October, there will be 12 videos that supplement the book’s text and graphics.

“So what we’ve got now is a book with plenty of instruction, plenty of background information, some fundamental stuff with design and composition, a lot about watercolor; and we’ve got a supplement now where we’ve got this little Larry — the cartoon that’s on the cover of the book — with little versions of it inside and there are 12 of them” to correspond with the 12 videos, Larry said.

Larry Frates working on a watercolor.

“So, as of October, the people who buy the book will have access to 12 instructional videos in addition to the book, so that way, they’ve got the pictures, they’ve got the words, and if that doesn’t make sense, they’ve got the action. They’ll be able to see it from different points of view, especially like brush strokes. Instead of just seeing a hand holding a brush, they’ll be able to see how much pressure I put on the brush or how I twist the brush,” Larry said.

The videos will be password-protected, so owners of the book will contact Larry with verification of the purchase in order to get their password to unlock the video. Or, he said, people may want to purchase the video alone, “which means eventually you’re going to want the book.”

“Ideally,” he added, “it would be nice to do an e-book.” That would allow him to link a photo in the e-book with the accompanying video. “But technology-wise, I’m not there yet.”

While all of the writing is Larry’s, he wanted to include some students’ work as well as some photographs that readers can use in creating their own watercolors. Seven local photographers contributed three photos each to serve as subjects for the readers’ own experiments with watercolor. Those pages are followed by examples of Larry’s and his students’ works to show how diverse the interpretations and use of watercolor can be.

Those interested in the book may purchase it directly from Larry at www.larryfratescreates.com, or at the Belknap Mill. Copies soon will be available at bookstores as well.

Another way to learn more about the book is to meet Larry in person at a series of gallery exhibits. The Lakes Region Center for the Arts in Meredith is organizing gallery shows at local libraries as part of its public outreach goal, and engaged Larry for an exhibit at the Wolfeboro Public Library, running through Thursday, Oct. 7. On the final day of the exhibit, there will be a Meet the Artist event at 6 p.m. Larry will talk about his new book and do a painting demonstration.

Larry has future exhibits planned at the Meredith and Moultonborough public libraries.

Larry said he chose Wolfeboro for his first exhibit in the series because he was not as well-known there. “It would be a whole new audience,” he said.

Having been associated with the former Artisans on the Bay in Meredith, as well as other art groups in that town, his name is well-known in Meredith. He also has conducted two watercolor classes at the Meredith library.

As for Moultonborough, during his teaching days, he had served as an art teacher at Moultonborough Academy from its inception until its art department grew to three instructors.

With his background in teaching, Larry likes to describe watercolors as being “the adolescent of all mediums.”

“It’s similar to working with middle school kids,” he said. “Oil is pretty predictable, acrylic is pretty predictable, pen-and-ink is predictable; and watercolor, just when you think you’ve got it, it does something, and it challenges you … and basically, that’s what happens with adolescents.” They seem to have grasped a lesson one day, and the next day, they seem to have left everything they learned at home, and the teacher has to try another angle to get the lesson across.

Watercolor painting.

“I just think it’s a fun thing to do,” he said of watercolor painting. “It’s challenging, it’s simple, and in some cases it’s relaxing, and it will do what you know it will do. But then you reach a point where you want a challenge and so you try other things — it might be a different brush, it might be a new kind of paint, a new color. But I like the spontaneity of it, the challenge of it. It says what it has to say.”

The Belknap Mill is located at 25 Beacon Street East in downtown Laconia, NH; call 603-524-8813.

Golden Rule Farm Served as a State’s ‘Boys Town’

Stone columns and a historical marker on an abandoned road are the only physical remains of a unique program that aimed to prepare young men (and a few young women) for adulthood in the early 20th century, but the legacy of Franklin’s Golden Rule Farm lives on, meeting other needs, in the form of Spaulding Academy and Family Services in Northfield.

Boys of all ages received education and life skills at the Golden Rule Farm. (Spaulding File Photo)

Golden Rule Farm Served as a State’s ‘Boys Town’

By Thomas P. Caldwell

Stone columns and a historical marker on an abandoned road are the only physical remains of a unique program that aimed to prepare young men (and a few young women) for adulthood in the early 20th century, but the legacy of Franklin’s Golden Rule Farm lives on, meeting other needs, in the form of Spaulding Academy and Family Services in Northfield.

The intriguing story of the Golden Rule Farm actually begins 150 years ago with the establishment in 1871 of the New Hampshire Orphans’ Home, later known as the Daniel Webster Home for Orphans, on Elms Farm, the estate owned by Daniel Webster’s family and the place where New Hampshire’s famous orator and statesman grew up.

A young resident of Golden Rule Farm pitches hay. (Spaulding File Photo)

The Orphan’s Home was established through the efforts of Rev. Daniel Augustus Mack, who had been orphaned at age seven and who, as a chaplain during the Civil War, had received entreaties from dying soldiers to look after their children. The orphanage was established by an act of the state legislature in 1871, and the board of directors purchased the Webster farm that October.

Two stone gate posts are all that remain of the Golden Rule Farm in Franklin, forced to relocate when the Franklin Falls Dam was built. (Tom Caldwell Photo)

The Golden Rule Farm grew out of the work of another pastor, Rev. George W. Buzzell, who received a gift of the 100-acre Roberts Farm in 1901. It had been the home of Daniel Webster’s sister. Buzzell established a cottage-style housing arrangement for orphans and taught them life skills in what first was known as the Bradley Memorial Home. When, in 1914, it was joined to the Golden Rule Homestead, which increased the size of the property to 400 acres, it became the Golden Rule Farm.

Situated in the Pemigewasset Valley between the towns of Hill and Franklin, it gave orphans the opportunity to experience farm life. Ledgers from the early years contain entries about the children brought there from homes where there was an unwed mother or a widowed father unable to care for his children, or a child was simply left on the doorstep.

A sample entry: “a babe 8 months old — Husband gone — Child illegitimate.”

Golden Rule Farm adapted as the need for orphanages declined and the needs of urban children facing corrective situations grew, and the rehabilitation of juvenile delinquents became a major focus. Golden Rule Farm began taking in troubled boys who had problems at home or run-ins with the law, giving the place the reputation of being New England’s Boys Town — a reference to Father Flanagan’s Boys Home where the priest offered an alternative to reformatories and other juvenile facilities.

Nurses care for some of the orphans in this file photo in the archives of Spaulding Academy and Family Services.

At a time when many such facilities abused child inmates or used them as slave labor, the Golden Rule Farm took a caring approach. The children were put to work, but the emphasis was on teaching them useful skills. They received an education, participated in group activities, and learned what they would need to know to make it in life. Records from Golden Rule Farm showed instances where the directors protected their charges from farmers looking to adopt a son with the likely intention of using the child as free labor. The administrators simply said no boys were available.

The work of Golden Rule Farm caught the attention of many people who would become supporters of the institution, including the actress Bette Davis, who had a residence near Franconia in Sugar Hill, New Hampshire.

Residents of the Golden Rule Farm learned skills they could use later in life, including working with electronics. (Spaulding File Photo)

When the Franklin Falls Dam was built in 1939, it forced the relocation of Hill Village and the residences within the flood control area, and Golden Rule Farm was one of places forced to find a new home. That new home was to be situated on the Boynton and Holquist farms in Northfield.

At the time, Boston Herald writer Bill Cunningham wrote of the home’s mission and its plight:

The Golden Rule Farm is a project in the rehabilitation of the American boy — maybe repossessing would be a better word. It’s not a reformatory. It’s not a refuge for the afflicted nor the feeble minded. It takes strong, sound, manly, potentially valuable American citizens whose family background has gone to smash for some reason, and gives them what every kid in this land has need of if he’s to grow up loving it and believing it and ready to stand squarely in the harness for it — a real, warm hearted and very personal home. …

It faces a crisis of sorts at the moment. It has to move. Its current premises near Franklin are exactly in the way of a flood control project ordered by the federal government, and although it’s taken what should prove to be a better location near Tilton, it needs to fit up the new place with the necessary buildings and all, and, in the days of Aid to Britain, Help the Chinese, Buy Defense Bonds, and all the mighty and clamorous rest, the thin, clear call of a boyish American voice is likely to be drowned in the general confusion.

The necessary money came through, and Golden Rule Farm had its new home. Then, in August 1941, there was a devastating fire that broke out in a hay barn. Again, Cunningham wrote of the problem:

The breeze threw the flames swiftly over the bunk house next door where some 30 of the young gentlemen were quartered and the whole thing went in a roar while the little fellows stood helplessly across the road, many of them in tears.

The Golden Rule Farm in Franklin. (Spaulding File Photo)

The Farm had insurance — all it could get — but you can’t get much on farm property completely away from fire plugs, and this was not only complete loss of quarters. It was loss of clothing as well. … That fine and friendly place has 50 boys to care for and at present it has accommodations for only 15. The rest are currently living in tents provided by the Red Cross and friendly people of Tilton and Franklin. … The neighbors and the kind folks of New Hampshire in general have rallied around in this way and that, but cold weather’s coming. Those kids need a couple of buildings. … How about some quick and real help for our very own?

Once again, supporters did come through, and Golden Rule Farm was able to remain in operation until 1958 when it merged with the Daniel Webster Home for Orphans and became Spaulding Youth Center. The merger had been talked about for years, and in April 1958, the boards of directors of both institutions appointed committees to work out the details.

Like its predecessor institutions, Spaulding Youth Center adapted to the changing needs of children. In 1970, Spaulding adopted behavior management as its major focus, reflecting the needs of children with emotional problems. In 1988, it completed construction of the Cutter-Wiggins Trauma Unit, aimed at helping those with traumatic brain injuries.

Troubled boys could find structure and friendship at the Golden Rule Farm in Franklin. (Spaulding File Photo)

In 2004, Spaulding began assisting with the placement of children needing foster care and it later would take on the training of people interested in becoming foster parents. In 2012, Spaulding opened a new, high-performance school able to provide specialized programs and services for children and youths, including those with autism.

The last couple of years marked a new phase for Spaulding when it opened a new cottage called Wednesday House in 2020, to provide a place for students whose homes were unsafe due to their parents’ drug use or neglect. The students are able to attend public school during the day but have a safe place to stay when school is not in session.

In short, from the time the New Hampshire Orphans’ Home opened, the institution now known as Spaulding Academy and Family Services has identified and responded to the biggest unmet needs in the state of New Hampshire. Golden Rule Farm was an important part of that journey, and those former residents who are still living today recall their time there with fondness.

Golden Rule Farm taught the young residents about farm life and gave them skills they could take into adulthood. (Spaulding File Photo)

Painting And Loving It

Artists often never learn where their works end up, so they are always surprised when they hear from a buyer or the family member of someone who had bought a painting years ago.

Painting And Loving It

By Thomas P. Caldwell

Gerri Harvey painting

Artists often never learn where their works end up, so they are always surprised when they hear from a buyer or the family member of someone who had bought a painting years ago.

That was the case for Gerri Harvey, a Laconia landscape artist who is currently working on a large commissioned painting for a woman in Texas who previously purchased one of her paintings online. Before online sales, when paintings sold mainly through galleries, the purchaser and destination usually remained unknown.

That was the case with her first sale, an 11x14 oil painting of birch trees by a stone wall.

“It was sold for $35 during an art association show at the Belknap Mill around 1982,” Gerri recalled. “I had entered it in the novice artist category. I had no idea who bought it or where it ended up.

“Last year, I got a contact via my art website from the daughter of the woman who had bought it while vacationing here from Connecticut all those years ago. Her mother was now deceased and the daughter told me her mother loved the painting and was sure I was destined to become a very good painter. She sent me a photo of the painting. I have come a long way!

Gerri's studio

“The daughter now owned the painting and wanted to come full circle and purchase one by me as a way to honor her mother’s memory and love of the Lakes Region where she often vacationed. She bought one she saw on my website and I shipped it to her during COVID. I sent it priority mail with tracking. It took five weeks to arrive because it went all the way to California before finally arriving in Connecticut.”

Gerri says that, over the years, she has heard from a few other people who inherited older paintings she had done. “In one case, a nice man delivered one of them to me that he had found in an estate sale, thinking I might like to have it back,” she said.

She estimates that she has sold hundreds of paintings over the years, and said that, last year, between sales and commissioned pieces, she sold around 50 paintings.

Some artists avoid trying to create a painting that reflects someone else’s vision, but in the case of the Texas woman mentioned above, Gerri said, “If the request is within the genre I like to paint, and the person already likes my painting style, I enjoy giving it a go.”

The client had purchased a smaller piece through an online art event and contacted Gerri about doing a larger piece that would represent her “dream” retirement place. Gerri worked from the woman’s description, creating two 8 x 10 studies as a starting point for the actual painting. One reflected an actual scene in Gilford and the other was a composite painting that Gerri created by interpreting the woman’s vision. She sent photos of the two studies so the woman could decide which she wanted to have done as a larger painting.

Gerri said she began painting in her early 30s. She took weekly group classes in oil painting with the late Loran Percy in his Gilford studio.

“My classes were ‘Mom’s night out’ when my children were small,” Gerri recalls. “Loran was an inspiring teacher and I was his student for about two years.”

Later, she took some group classes in watercolor with Laconia artists Larry Frates and the late Betty Jean Maheux.

“I was working as a registered nurse and raising a family, so I was only an occasional dabbler and hobby painter, but I enjoyed it, painting at home on my kitchen table,” she said.

When her children were grown, she decided “to see where I could go with my painting.” She took workshops with a few nationally known painters, including watercolorists Ted Nuttall and Stan Miller, floral oil painter Nancy Medina, and Tom Hughes, who does plein air oils. She also attended workshops locally with Dennis Morton and Carole Keller.

“I have a whole library of art books, too,” she said. “One of the joys of being retired is having the time to paint and learn, and I am still learning.”

A Fine Day

She has signed up for a three-day oil painting workshop with Vermont artist John MacDonald, scheduled for this fall.

Gerri has gone through several “art periods” — trying stained glass, quilting, silk painting, paper collages, fabric collages, rug-braiding, rug-hooking, jewelry-making, and clay.

“At one point, I decided I had to choose just one because who has the time or space to do it all?” she asked. “I chose to focus on painting because I love painting so much, and for the past 10 years since retiring, I have painted a lot. Well, I just picked up rug-hooking again, too, so I guess it’s really two.”

She has painted portraits, animals, and florals, but said she is particularly interested in doing landscapes and lake scenes.

“There is so much inspiration around me right here in New Hampshire,” she commented.

While she started with oils and watercolors, Gerri switched to acrylics when her daughter was little and wanted to paint with her mother. Painting with oil requires using solvents that can be harmful, while acrylics have a polymer base and are not only safer but also light-fast and permanent when dry.

“They look much like oils but handle quite differently in that they dry very quickly, unlike oils which take weeks, making blending and layering a longer process with lots of waiting time,” she said. “I like to paint right along, sometimes completing a painting in a day or two, so acrylics actually suit my painting style very well. I do still use oils and watercolors occasionally, though.”

Her daughter enjoyed painting so much that she majored in art at college, and today she is a successful watercolor artist living in western Massachusetts.

Four years ago, Gerri met pen-and-ink artist Steve Hall through an art group they both belonged to, and where they were gallery-sitters for an entire day. Both were widowed after long, happy marriages, and Gerri said, “it was the beginning of our friendship that became our chapter two love.” He wanted to learn to work with acrylics and took lessons from Gerri.

Reflecting On Summer

They both sold their respective houses and bought a new house together three years ago, sharing studio space downstairs.

Gerri said she carries her paints wherever she goes so she is prepared to capture a scene. She also takes reference photos and notes for later painting efforts.

“I have done painting off the coast of Rhode Island where I grew up, Maine, Vermont, Massachusetts, New York, Florida, South Carolina,” she said.

“At the start of COVID, we bought a tiny camper so we could still go places to visit and paint,” she continued. “I am new to camping and, though it’s small, it has every convenience except space, so paint supplies go in the car.”

Gerri also gives art lessons — originally through VynnArt Gallery in Meredith as well as private lessons at her home studio.

“Since I don’t have an academic background in art, I teach by the ‘show-and-tell’ method, and I think it really appeals to adults,” she said. “It is how I learned, and how most painting workshops are structured. I am organized, patient, and encouraging as a teacher. I believe that most people can learn to paint reasonably well if the desire is there; you don’t have to be a Rembrandt to create a good painting, and the creative enjoyment itself is reason enough to paint.”

She also sold her own paintings through VynnArt Gallery. When that divided into three galleries under one roof in January, it became The Galleries at 30 Main: VynnArt Gallery, the Moreau Gallery, and the Ferreira Gallery.

“I stayed on,” Gerri said, “and now I am part of Moreau Gallery.”

Gerri also is part of the 15-member Fusion Gallery, an online gallery that makes her works available to collectors all over the world. She participates in an online sales event every other month.

“I started painting over 40 years ago and I am still learning,” Gerri said. “I feel pretty passionate about painting and look forward to my studio time. I paint a few days a week, sometimes only for an hour, sometimes all day. I still find so much challenge and joy in it, and I like helping others find that spark, too.”

View her works at The Galleries at 30 Main in Meredith, the gallery wall at Wayfarer Coffee Roasters in downtown Laconia, Fusion Gallery on Facebook, on her website, gerriharveyart.com, and by appointment at her home studio in Laconia.

Gypsy Carver Brings Ideas to Life

Homeowners looking for something unique to place in their yards have someone to turn to in Mike Thomas, a chainsaw artist operating as Wicked NH Carvings in Bristol.

Gypsy Carver Brings Ideas to Life

By Thomas P. Caldwell

Homeowners looking for something unique to place in their yards have someone to turn to in Mike Thomas, a chainsaw artist operating as Wicked NH Carvings in Bristol.

“If you can show me an idea, I can carve it,” says Mike, suggesting that potential customers check out his work on Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/carverit), then Google images of what they’re looking for. “Send the one you like the best,” he says. “Customers can ask for anything.”

Also a freehand artist, Mike says, “If they can make me understand what they’re looking for, I can sketch it for them. Give me a broad idea and I’ll show 20-30 examples.”

While he has operated Wicked NH Carvings for just three years, Mike says he has been carving most of his life — ever since his uncle bought him a Dremel, a handheld rotary tool with a variety of attachments and accessories.

“I come from a family of gypsies,” he says. “I was born in 1972 in Lincoln, Maine, but my family traveled everywhere. I grew up in Laconia, but we traveled all over the place, to every state except Hawaii and Alaska.”

He picked up and improved upon his carving skills from the people he met on his travels, as well as seeking out videos on YouTube. Among those who provided inspiration was Peter Toth, a Hungarian-born artist who created wooden sculptures to honor Native Americans in every state, including the 35-foot “Keewakwa Abenaki Keenabeh” or "The Defiant One” in Laconia’s Opechee Park. (That 12-ton red oak sculpture was removed in 2019 after rot made it a hazard.)

“I love doing anything Indian-related, and do a lot of reading on Abenaki tribes,” Mike says. He also does motorcycle carvings, including custom Harley bars for houses. His own mailbox is in the form of a motorcycle.

Most of the work is done with a chainsaw, but he uses a die grinder with special bits to do the more intricate parts of the sculpture.

Before establishing Wicked NH Carvings in 2018, he had worked at a variety of jobs, including as a tattoo artist. (He also has operated a detail shop and a skateboard shop.) Then, eight years ago, he broke his spine.

“Once I broke my back, I couldn’t do anything,” he says. “To this day, I can’t do tattoos because you’re leaning over a chair.”

It took five years after the accident for him to carve again, but he found it was a great way to become active once more.

Origins

Woodcarving is a form of art dating back centuries, to soon after early man started shaping wood to make primitive tools by using sharp rocks and bones. It didn’t take long to combine art with function, with the earliest examples often used for religious purposes.

Knives and chisels would provide the most common means of shaping wood, but, according to lore, a logger named Joseph Buford Cox noticed a timber beetle larva chomping through a log in 1946, and noted that the creature cut both across and with the grain of the wood. He decided to duplicate that motion in a steel chain, and the modern chainsaw was born in 1947.

Just six years later, “Wild Mountain Man” Ray Murphy used a chainsaw to carve his brother’s name in wood for what is perhaps the earliest example of chainsaw art. Then, in 1961, Ken Kaiser created the Trail of Tall Tales in Northern California, carving large redwood logs in shapes on a Paul Bunyan theme.

By the 1980s, there were traveling chainsaw carvers who used their trucks as galleries, and chainsaw carving shops started appearing along the roadsides. Chainsaw artists appeared at country fairs and carving contests began to appear.

In the 1990s, chainsaw carving gained popularity as an art form.

For Mike Thomas, “that carnival gypsy blood” in his family made the house on Route 3-A South in Bristol the perfect spot for a business. “I love that the house is right on the road,” he says. “I have 978 feet of road frontage and that makes my business that much more successful.”

Mike says that, when he and his wife first got together, they got an apartment in downtown Bristol. “We always said, if we bought a house, we’d come back to Bristol to do it.” Nine years later, they did just that, coming back to New Hampshire from Massachusetts where he had operated the skateboard shop. Now, traffic passing by will salute him.

“Loggers know me, and they honk the horn. People at the factory in Franklin are used to seeing me out there carving, and when they see a carving in the back of a truck they pass on the freeway, they’ll say, ‘I saw your carving go by.’”

Having coached T-Ball at the Tapply-Thompson Community Center in Bristol, local people have come to know him, which also has helped as he built his business. He is known for his support of local charities such as the Franklin Animal Shelter. He said he donates to 10 charities in the area each year.

Working Through COVID

Word of mouth has helped him while other businesses have suffered during the coronavirus pandemic. Mike says last year was his best year yet, and he has had a hard time keeping up with orders.

Working with heavy logs was a problem until a local welder built a log crane, which allows him to stand logs up for carving.

He prefers using seasoned white pine for the sculptures, buying the wood from Brett Robie’s sawmill in Alexandria, as well as from other local millers. “I like white pine,” he says, “because of the ease of carving. And if it’s seasoned right, any cracking is very small — what are called hairline character cracks. They’re only small cracks, so it makes for easy maintenance.”

He will carve hardwood by special order.

He said that 80 percent of his work is done on-site, but he is willing to go out into the community to carve on people’s property if they wish, and hopes to do more of that. An example of the custom work he has done is a nine-foot cross that a Browns Beach Road customer ordered in memory of a granddaughter who had died. The sculpture, which overlooks Newfound Lake, features the girl’s spirit walking behind and emerging in front with a cat. He also carved a large eagle with wings spread, sitting on a perch.

Carvings have included weasels, crows, and rabbits — just about every animal, he says. “I’ve done I don’t know many eagles and bears — hundreds if not thousands.”

He also has done a lot of carvings for veterans, including for Wounded Warriors, featuring soldiers and symbols such as a flag or an eagle.

Mike says he can block out and put hair on a bear in about eight hours, while the painting and staining can take a couple of days.

“I typically do four or five carvings at a time,” he says.

Because he does not have the overhead that many chainsaw artists have, he said his prices tend to be lower — about $250 for a three-foot-tall bear and $1,000 for a six-foot bear. “It depends on the complexity,” he says.

His carvings have gone to seven states, including New York and Connecticut. He has a request to do a 16-foot-long center post for a log cabin in Pittsburg, New Hampshire, that would feature bears and owls, and he hopes to do some carving along the Winnipesaukee River in Franklin where the city is developing a whitewater park. “I would love to volunteer to do that; I would love to jump on the river and carve along it,” he said, noting that the park is seen as a key to Franklin’s revitalization.

“Nothing’s really difficult,” he said of his work, “it’s just a challenge. The most difficult one is the one I haven’t done yet.”

WinniOpoly:

The game of Monopoly is one of the most familiar board games, dating back more than 100 years, to The Landlord’s Game, designed by Elizabeth Magie. Its modern version, credited to Charles Darrow and now owned by the Hasbro company, appeared in 1935.

WinniOpoly:

The fun and colorful new game was the idea of Kathy Tognacci.

How About A Game Of WinniOpoly?

By Thomas P. Caldwell

The game of Monopoly is one of the most familiar board games, dating back more than 100 years, to The Landlord’s Game, designed by Elizabeth Magie. Its modern version, credited to Charles Darrow and now owned by the Hasbro company, appeared in 1935. The game’s popularity has spawned several modifications and updates over the years, with Hasbro announcing in March that it is looking for consumers to help determine new Community Chest cards for yet another version, to be released this fall.

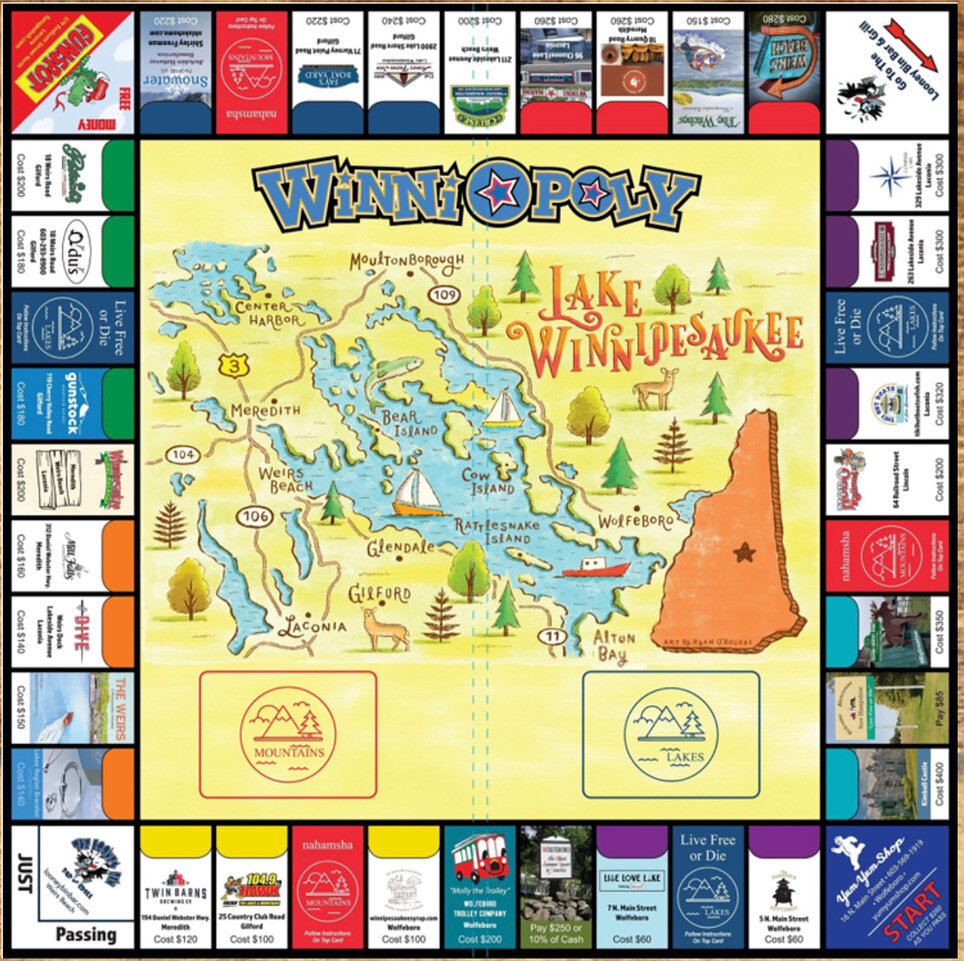

WinniOpoly

Meanwhile, local versions of the game, typically designed as fundraisers for towns or chambers of commerce, have been produced over the years, including 1985’s Follow The Mount — a Lake Winnipesaukee version based on the ports of call of the flagship MS Mount Washington. With Follow The Mount no longer available, there was an opening for a new local game, and Kathy Tognacci, who owns three gift shops in the Lakes Region, came up with WinniOpoly.

Kathy says she got the idea for WinniOpoly after seeing a Facebook posting about the old Follow The Mount game. “Something just clicked, and I said, ‘Why wouldn’t we have something current?”

Kathy did an online search to find out who makes custom Monopoly games and settled on a company in Georgia that would help her figure out how to set one up.

“It’s just going to be a fun game, featuring Lake Winnipesaukee, and my goal was, let’s get a really cool map of the lake in the middle of the Monopoly board and then all around the board, put all the fun local businesses,” she recalled. “So every morning I would get up with my cup of coffee and I started laying [it] out.”

She needed to secure permission from each business on the board, and started contacting them by email. “The people I picked were people that show up at our stores, people I knew, and businesses that do good deeds in the area, like, for example, Patrick’s” which raises money for the Lakes Region Children’s Auction. “I said, obviously, I would love them on the board; they’re across the street from me [in Gilford] and they bring me a lot of business year-round, so that started the whole process.”

Gathering the commitments and laying out the board took about three months. The game board included such places as Kimball Castle in Gilford, Funspot in Laconia, and the Yum Yum Shop and Molly the Trolley in Wolfeboro. “Molly the Trolley was an awesome fit for one of my railroads,” she said.

In place of “utilities” on the board, Kathy put in two books by Andy Opel, “The Weirs: A Winnipesaukee Adventure” and “The Witches: A Winnipesaukee Adventure.”

“I really made it custom to the lake and made it really fun,” she said.

“So then the board is coming together and I’m thinking the middle of the board, it really, really has to be something that stands out, so it had to be a picture of the lake, and I was trying to do it so it would be fun and colorful.” Her search led her to a Yankee Magazine article on the “magic wonders of Lake Winnipesaukee” which featured a map of the lake by Ryan O’Rourke, a freelance illustrator and associate professor of Art and Design at New England College. She ended up purchasing rights to his lake illustration. “It really makes the whole board,” she said.

In purchasing the rights to Ryan’s map, she also obtained large, signed copies of the illustration that she could frame and sell in her shops. “It’s a great little map and it’s fun,” she said.

It took three months to put the game together, and she decided to upgrade the playing pieces from plastic to pewter “to make it a bit nicer, because we weren’t going to make a cheap game,” she said.

O October 29, after she signed off on the final proof and placed the initial order of 500 games, she thought she had better gauge the public interest. “So right before I closed the store, I shared the proof of the WinniOpoly game on our Facebook page built for the Gilford Country Store. And I said, ‘Coming soon — Who wants one?’ So people were like, ‘Oh, my God, I love it!’ and I just said, ‘Reserve one here.’ … So that was at 6 o’clock. By 6 o’clock in the morning, when I woke up the next morning for my coffee, and I looked at our social media, we had sold all 500 of them in 12 hours.”

While most of the comments about the game were positive, there was one negative comment that “kind of stuck out to us. … ‘How come Alton Bay isn’t on the map?’”

The town had not been included on Ryan’s original map, but Kathy quickly realized what an important omission it was. “So the next day I reached out to Ryan …. ‘What would it take for you to take that map and just put those two words in that spot?’ ” He agreed, and when she ordered the next 1,000 games, Alton Bay became part of the board.

It took 12 weeks of production time for the games to arrive — too late for Christmas — so for those who wanted to give them as gifts, Kathy had small versions of the WinniOpoly board printed and placed them in gold boxes “like the Willy Wonka gold ticket.”

Kathy said, “People came and pre-bought hundreds of games to put in the stocking and give to people.”

She noted that the omission on the first 500 copies of the game made them more valuable to collectors, prompting her to set aside 50 of them for that purpose. Meanwhile, 2,000 games now have commitments and she has shipped WinniOpoly to 20 states.

The game is available at Kathy’s three stores: Gilford Country Store, across from Sawyer’s Dairy Bar on Rt. 11 in Gilford; Nahamsha Gifts at 63 Main Street in Meredith; and Live Love Lake at 15 North Main Street in Wolfeboro.

Sampling Something Sweet

The boiling of sap to make maple syrup is one of the lessons the indigenous people of the New World taught the early settlers arriving from Europe, and today those lessons remain the basis for New England’s maple syrup production. New techniques have been brought into play to make the operation more efficient, but, at its core, maple syrup production today is much the same as it was in the early days.

Sampling Something Sweet

By Thomas P. Caldwell

Walker’s Sugar Shack in Bristol. (Courtesy Photo)

The boiling of sap to make maple syrup is one of the lessons the indigenous people of the New World taught the early settlers arriving from Europe, and today those lessons remain the basis for New England’s maple syrup production. New techniques have been brought into play to make the operation more efficient, but, at its core, maple syrup production today is much the same as it was in the early days.

It still takes roughly 40 gallons of sap to produce one gallon of maple syrup, and collecting that sap depends upon the weather.

“To get the good sap ‘runs’ it needs to be below freezing at night and mid- to upper-40s during the day,” says Jason Walker who, with his brothers, Jeff and Joe, began Walker’s Sugar House in Bristol as a hobby in 2002.

“It seems early to start talking about maple season, given the current weather,” Jason said when contacted in mid-February. “We [have] started tapping the trees and the extended forecast is calling for some warmer temperatures … so we are optimistic spring is on its way.”

Classic sap collection is done with taps and buckets. (Courtesy Photo)

Walker’s Sugar House normally starts tapping the trees in February.

“Normally we get a few decent sap ‘runs’ towards the end of February, first of March, but every year differs slightly,” he said. “Everyone always asks how the sap season is going to be, and I always say I’ll tell you at the end of April! It is so hard to predict and really depends on the weather in March and April.”

He continued, “It is not so dependent on what the weather has been, but more on the cold nights and warm days during March and the first part of April. Usually the crazier the ‘up and down’ weather we get in March and April leads to a good sugaring season.

“Last year, we began the season during the last week in February and ended the second week in April, making for an exceptional year for syrup production.”

Normally, sap from the maple tree contains about two percent sugar, but in recent years, many producers have said the sugar content has declined to one percent. Jason says it is not unusual for the sugar content to vary from year to year and throughout the season.

Although Walker’s Sugar House has been actively producing syrup only since 2002, maple production on the Walker Farm has a long history, starting with Jason’s grandparents, Lois and Chester Walker Sr. They produced maple syrup off and on over the years, and Chet Walker Jr. produced syrup on the farm for a few years after returning home from college in 1970.

The current sugaring operation started with just a few hundred buckets, but today it has grown to more than 2,700 taps, using modern tubing and vacuum collection systems.

“Over the years, there has been a lot of technological advancements in maple syrup equipment and processes,” Jason says. “The sugar house started boiling on a 2-by-6 standard evaporator, which was upgraded to a 3-by-10 high-efficiency model. Other upgrades since 2002 include the use of a reverse-osmosis system and vacuum pump collection.

“With all the technological advancements, the sugar house still boils with wood,” he said.

Vacuum tubing allows syrup producers to bring the sap to large collection containers, rather than having to carry sap from the trees a pail at a time. Reverse osmosis can remove as much as two-thirds of the water in the sap before it is boiled, reducing the boiling time and the associated energy costs.

Jason says that, in an average year, Walker’s Sugar House produces about 1,000 gallons of maple syrup.

The modern evaporator condenses the sap into the maple syrup that customers want. (Courtesy Photo)

Walker’s has been a New Hampshire Seal of Quality Producer since the state started the voluntary program. New Hampshire Department of Agriculture inspectors verify that producers subscribing to the program are maintaining high-quality standards through periodic inspections.

The Walkers will be welcoming visitors to the Sugar House on the weekend of March 20-21, between 10 am and 3 pm, offering maple syrup, along with other maple products, for purchase. Maple products also are available at Walker’s Farm Stand during the summer months. To purchase syrup and other maple products at Walker’s Sugar House, call 603-744-8459 or email walkerssugarhouse@gmail.com to set up an appointment for pickup.

Alden Walker, a fourth-generation farmer, drives a tap into a maple tree. (Courtesy Photo)

For a list of sugar houses that produce maple syrup, please visit www.nhmapleproducers.com. (March is NH Maple Month; typically, many sugarhouses are open to the public, but due to this year’s Covid-19 restrictions, please call ahead to all locations.)

More about maple syrup

According to www.nhmapleexperience.com, Native Americans were the first to discover that sap from maple trees could be turned into maple syrup and sugar. We cannot be certain what the process was like those many years ago, or how the discovery was made, but maple sugaring has been going on for generations.

Today, the maple syrup production season generally runs from mid-February (or a bit later) until mid-April. The process, in simple terms, goes like this: sap in maple trees is frozen during the cold winter and when temperatures rise a bit, the sap in the trees begins to thaw. It then starts to move and builds up pressure in the tree. If you have noticed sticky sap oozing from any cut in a maple tree, this is the sap that is used for maple syrup production. Ideal conditions for the sap to flow are freezing nights and warm, sunny days, which create the pressure for a good sap harvest.

The classic New England maple scene with sap buckets on the tree. (Courtesy Photo)

If you drive around the state, you are likely to see buckets and plastic tubing around maple trees here and there. This is how maple producers tap the sugar maples. They drill a small hole in the tree trunk and insert a spout, and then a bucket or plastic tubing is fastened to the spout. If you assume the sap dripping from the tree looks like amber or darker colored maple syrup, you would be wrong. The sap at that point is clear. Once collected, it is taken to the sugarhouse and boiled down in an evaporator over a very hot fire. Steam rises and the sap becomes concentrated until eventually is turns to syrup. It is taken from the evaporator and filtered, graded and bottled.

Most of us love the taste of maple, but as those who make maple syrup will tell you, it is a long process and sometimes you stay up all night tending to the syrup. You watch the weather; you know that certain temperatures and conditions will make for a better season of maple syrup. You tap the trees, you tend to the sap house, you stoke the fire and you do it again and again.

Maple producers in New Hampshire love what they do, from opening up the sap house and getting everything ready for a late winter/spring season of maple syrup production to the first bottle of sweet maple syrup they produce each year.

Cold Weather Promises Good Ice for Fishing Derby

With a few exceptions, this has been a pretty mild winter in the Lakes Region, raising fears among some fishermen that the 42nd annual Great Meredith Rotary Ice Fishing Derby would not take place. Just a month ago, very little ice appeared on New Hampshire lakes, but in late January the temperatures plunged to signal that the derby should be able to go on as planned during the weekend of Feb. 13-14.

Cold Weather Promises Good Ice for Fishing Derby

By Thomas P. Caldwell

Hesky Park in the Meredith will be the place to be when not out on the ice hoping to hook the largest fish in one of seven categories during the Great Meredith Rotary Ice Fishing Derby on Feb. 13 to 14. Courtesy photo

With a few exceptions, this has been a pretty mild winter in the Lakes Region, raising fears among some fishermen that the 42nd annual Great Meredith Rotary Ice Fishing Derby would not take place. Just a month ago, very little ice appeared on New Hampshire lakes, but in late January the temperatures plunged to signal that the derby should be able to go on as planned during the weekend of Feb. 13-14.

This year’s derby will offer more than $50,000 in prizes, with a first prize of $15,000 in cash, a $5,000 second prize, and a $3,000 third prize. The five heaviest fish each day in each of the seven categories will receive prizes of $50, $200, $150, $100, and $50, and there will be several ticket stub cash drawings each day.

There also will be two “Grand Cash Drawings” for $5,000, selected from derby ticket stubs, whether or not the person has fished.

Contestants are able to fish any New Hampshire lake to land their prize-winner, with last year’s entries coming from 25 bodies of water.

The Meredith Rotary Club held its first ice fishing derby in 1979 and the derby has continued every year since, although the club was forced to postpone it a few times to wait for better ice.

“Given the current weather forecast, it’s looking like there will be no need to delay,” said Tiffany Pena in response to questions about the lake conditions in late January. “We are monitoring the situation and any decision to postpone will be made two weeks prior to the derby.”

During the early years of the derby, the club provided merchandise prizes, such as a boat and trailer, but derby officials learned that most winners would have preferred cash, and many of them sold their prizes after receiving them. As a result, the club switched to cash prizes — in amounts that have increased over the years.

Other changes that have occurred during the life of the derby include which fish qualify for prizes. The grand prize used to go to biggest tagged rainbow trout, but the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department asked the derby to relieve the pressure on the trout population, so the club expanded the list of acceptable fish to seven species. Today, the list includes Cusk, Lake Trout, Pickerel, Rainbow Trout, Yellow Perch, White Perch, and Black Crappie. The Black Crappie had not been on the list of acceptable fish prior to 2011.

One other change the club made was to replace its old trailer with a new one built by Rotary Club members.

This year’s derby changes the Saturday weigh-in deadline to its original time of 4 pm. The derby also has put in place special rules to meet state health guidelines during the coronavirus pandemic. Face coverings and physical distancing will be required of those in line to purchase tickets at Derby Headquarters, to enter fish at the weigh-in station, and to purchase merchandise at the club trailer.

To allow for longer lines, anyone waiting to enter a fish at the weigh-in station at the deadline will be permitted to continue through the line and have the fish weighed. The club website, MeredithRotary.com, will include a Min-Max report that is updated with each fish entered. Having that information will help people decide whether to go to Derby Headquarters to enter a fish. The fish board itself will be “virtual” this year, appearing on the club website.

Another change under the pandemic guidelines is that the grand prize drawing will be an online streaming event, with links on the website and on Facebook. A recording of the drawing will be placed on the club website as well. To qualify for the top three prizes, the angler must have had the largest fish in one of the seven categories and have a valid derby ticket. An angler can be entered in the Grand Prize drawing only once, no matter how many fish that person has caught.

The club has canceled the kids’ fishing clinics, but will allow youths with derby tickets to enter fish for prize drawings, whether or not they have cash-prize-winners.

The traditional fish board will be replaced by a virtual board this year to show the largest fish turned in at the Great Meredith Rotary Ice Fishing Derby this year. Courtesy photo

The names of cash raffle winners will be posted to the club website as they are drawn, and winners will be notified by telephone.

In announcing the changes under COVID-19, the club emphasized what doesn’t change: Everyone needs a ticket to win; all prizes will be awarded; anglers can fish any public water body in New Hampshire; Derby Headquarters will still be in Hesky Park in Meredith; Derby merchandise will be available for sale; and prizes can either be picked up at Derby Headquarters or they will be mailed to winners.

Good luck, and happy fishing!

(Editor’s note: information as of press time, but please check the Rotary website at www.meredithrotary.com for updates on weather and ice conditions.)

Sidehillers Boast Scenery and Social Connections

A wide expanse of open fields and mountain views in the Whiteface-Intervale area of the state is one of Ross Currier’s favorite places to ride a snowmobile.

“It’s the scenery,” he says, that makes the 25 miles of groomed track maintained by the Sandwich Sidehillers Winter Trails Club so special.

Sidehillers Boast Scenery and Social Connections

By Thomas P. Caldwell

The Sandwich Sidehillers Travel Club groomer clears a section of trail. (Courtesy Photo)

A wide expanse of open fields and mountain views in the Whiteface-Intervale area of the state is one of Ross Currier’s favorite places to ride a snowmobile.

“It’s the scenery,” he says, that makes the 25 miles of groomed track maintained by the Sandwich Sidehillers Winter Trails Club so special.

The Sandwich Sidehillers is but one of the many snowmobile clubs that maintain a total of 6,800 miles of groomed trails in New Hampshire, assisted in part by the registration fees that members pay to the state. Unlike most clubs, though, one-third to one-half of its membership is snowshoers/cross-country skiers. That is by design, says Ross, who is serving his fifth season as president of the small club.

Bob Condit operates the trail groomer. (Courtesy Photo)

“The original group knew it was going to be an uphill battle to try and get landowners to share their properties with snowmobilers, and the more [the club] appealed to the masses of the town of Sandwich, the better the chance to get the landowners’ support,” he said.

Today, the club has a “really good” relationship with the landowners, Ross says. “Basically, we keep in touch with them on an annual basis to update their permissions. Generally, the people that started the club treated them so well, there’s never much hesitation to renew. I think it’s also that our trails have been situated here for so long, and there are some very large landowners that are used to sharing their property with other uses.”

The club formed in 1998, with Dan Peaslee serving as its first president. The Peaslee family had taken the lead in operating the club over the years but decided it was time for others to step up to keep the club going. They put out a challenge, saying that either someone else from the town would need to take over, or it would have to be operated by a neighboring club.

“I’d retired that year and said, well, I’ve got nothing to do and have the free time, so I jumped in,” Ross said.

Beginning in late November or early December, work teams meet weekly on Saturday mornings to clean up the trails, clearing blowdowns and trimming branches.

The Peaslee Bridge crossing on a snowmobile trail maintained by the Sandwich Sidehillers Trails Club. (Courtesy Photo)

The Sidehillers’ trails stretch from Sandwich Notch to Whiteface-Intervale. Ross notes that it is a ride-in, ride-out system due to a lack of connecting trails.

The snowmobile trail leading from Whiteface Intervale Road to Bennett Street In North Sandwich. (Courtesy Photo)

“We lost a trail from Sandwich Notch Road to Squam Lake,” he said. That removed five or six miles from the original system. That section included a town road that never used to be plowed, but with increased development that brought in more lakefront property owners, the town started maintaining that road for winter traffic.

“Our neighbors to the west, the Squam Trail Busters, would like to see that get opened up because it would mean a lot to them, too,” Ross says.

On the eastern side, the Ossipee Valley Snowmobile Club lost its east-west pass, isolating the Sidehillers from them, as well.

“We’re almost landlocked,” Ross said.

There is limited parking at the end of Sandwich Notch Road, with room for two or three trailers, but most snowmobilers ride in from the Plymouth area, he said.

Between five and six miles of the trail runs along the power lines, with the majority of it lying within the White Mountain National Forest.

“It bridges two ranger districts,” Ross said, adding that they have an excellent relationship with the rangers. The trails skirt the edge of the wilderness, and one trail leads up to Flat Mountain Pond.

“It’s a pretty technical ride,” he said of Flat Mountain Pond, noting that there is no groomed trail there. “It requires a lot of snow to make it open, and it’s a very sensitive area, about eight miles long. The fact that we have a trail there at all in a protected wilderness area is a pretty cool feature of our trail system. You have to be an experienced rider because it’s too twisty to get a grooming machine up there.”

Sandwich Trail

Open to New Members

While the club had in excess of 70 family memberships at one time, the number last year was 34, and because it’s such a small club, getting help for trail work remains a challenge, even though it’s not difficult work.

“One of the reasons I came in as president was the dwindling participation,” Ross said. “The same people were doing all the work, with no one else helping to carry the load.

“I learned a lot that first year. When half or a third of those members are non-snowmobilers, it’s hard to get a quorum for meetings and to conduct regular business. This year, it’s a real challenge because of COVID. The clubhouse is so small it’s hard to meet and maintain social distance.”

Working on the trails is another matter. “This is the perfect way to enjoy a morning outdoors in a socially distant way,” Ross says.

The spiked interest in boating over the summer may translate into greater interest in outdoor recreation this winter.

“You read about how snowmobile dealerships can’t keep machines on the floor,” Ross said, “so you’d think there would be more members.”

He noted that membership in clubs affiliated with the New Hampshire Snowmobile Association, such as the Sidehillers, qualifies for discounts on state registration fees. Those registration fees are important to trail maintenance, helping to cover the cost of grooming machines, which can cost a quarter of a million dollars.

“Redoing the tracks on our Tucker Sno-Pad was $20,000,” Ross noted.

Ross and Bob Condit share the main duties of grooming the trails.

“We put boots on the ground to see what needs to be done,” Ross said, adding that the Saturday morning trail details tackle one section each weekend prior to the start of the season.

Despite the club’s excellent relationship with the landowners who allow the trails to cross their properties, there is always a challenge from users who do not obey the rules.

“Last fall, we had somebody go out with a four-wheeler on the snowmobile trail, and the property owner threatened to shut it down,” Ross said. “Things like that have a tendency to resolve themselves in this community because it’s easy to figure out who he was. The club had to do a little special attention to the landowner to get us past that, but the landowners knew they could count on us.”

Cars park along the easternmost end of the trail at Whiteface Intervale Road. (Courtesy Photo)

A bigger problem is along the power line. “We had people go off — they love to see that fresh powder and go off the trail, and as soon as people start doing that, it sends others off the trails. Mountain sleds are probably the biggest offenders: They’re designed to go off the trails. We’re trying to figure out how to handle that across the state because that’s the biggest offender type rider,” Ross said.

Still, he said, snowmobiling — as well as snowshoeing and Nordic skiing — remain a lot of fun.

“I’ve gotten to know a lot of people through being part of this club that I’d never meet otherwise,” Ross said. “That’s one of the things: It’s social.”

The Sandwich Sidehillers Winter Trails Club meets at its clubhouse, located at 303 Wing Road in North Sandwich, sharing a driveway with Young Maple Sugarhouse. For more information, email sidehillers@gmail.com.