Last Night Rings in the New Year

The popular Carolyn Ramsay Band returns for a New Year’s Eve free performance at Last Night Wolfeboro at 4 p.m. at the First Congregational Church of Wolfeboro, located at 115 S. Main Street.

By Kathi Caldwell-Hopper

Saying farewell to the old year and welcoming the new is a way to begin fresh. New Year’s Eve is a fun time when area towns pull out the stops to make it a festive celebration. Families can spend the day – and evening – celebrating with games, music, food, crafts, and of course, fireworks at events in Wolfeboro, and other places in the Lakes Region.

A wonderful way to usher in the new year and say goodbye to 2025 is the Last Night event (now in its 9th year) in Wolfeboro. Visitors are invited to explore everything happening throughout Wolfeboro on Dec. 31 with morning activities to evening entertainment. This year’s Last Night lineup is packed with music, performances, games, and family-friendly fun.

Says Brenda Jorett, content and outreach consultant for the event, “It takes about eight to nine months to plan Last Night Wolfeboro. We develop the events over time, and we try to provide something for everyone. The day of the event, we have about 20 volunteers to man all the events.”

She continues, “Returning favorite this year are the Wildlife Encounters, the Carolyn Ramsay Band and Jason Tardy, a popular juggler.” These acts are just a few of the many talented performers that make Last Night Wolfeboro a must-attend event.

Start the day of Dec. 31 at 10 am (until noon) at the Great Hall in Wolfeboro Town Hall at 84 South Main Street with crafts by the NH Boat Museum; C3Brix - LEGO fun; Kingwood Youth Center, Yum Yum Shop gingerbread decorating; kiddie axe throwing and target games.

At 2 pm, Jason Tardy returns to Last Night Wolfeboro with his high-energy juggling performance on the Great Hall stage. This is followed at 3:30 pm with Wildlife Encounters live animal show, sponsored by The Children’s Center.

From 11 am – 4 pm, a fun Escape Room, developed and presented by The Resistance from the Kingswood Regional High School robotics team offers fun. There will be a morning sign-up (mandatory) at the Wolfeboro train station building, 32 Central Ave. in Wolfeboro.

Juggler Jason Tardy and partner will amaze the Last Night Wolfeboro audience at 2 p.m. at Great Hall, Town Hall during Last Night Wolfeboro on Dec. 31.

Kids love a good magic show, and Magic by George, hosted by Wolfeboro Library, will take place in the library’s Bradley Room at 12:30 pm.

Two bingo sessions will be hosted by the Wolfeboro Lions at Brewster Estabrook Hall at 80 Academy Drive off South Main Street at 1 and 2:15 pm.

A Marimba Mischief concert starts at 1 pm at the First Congregational Church of Wolfeboro, located at 115 South Main St. across from the Carpenter School in Wolfeboro.

For those who love – or want to try – ice skating, head to the Pop Whalen Ice and Arts Center at 390 Pine Hill Rd., Wolfeboro, adjacent to Abenaki Ski Area. The skating time is 2:30 to 3:30 pm.

A twilight performance by the Carolyn Ramsay Band, a Lakes Region favorite, will be held at the First Congregational Church of Wolfeboro at 4 pm. Don’t miss out on the opportunity to get rockin’ with this great band as you prepare to welcome in 2026!

You can also enjoy a tasty dinner for the entire family at the First Congregational Church of Wolfeboro with a 4 – 6:30 pm buffet supper; tickets are purchased at the door.

Following dinner, a First Friends & Family Trivia will begin at 6:30 pm with prizes, including a gift from the New Hampshire Boat Museum, and takes place at First Congregational Church of Wolfeboro.

Plan to end the day with a glorious fireworks display over Wolfeboro Bay off Town Docks, Wolfeboro, weather permitting; (if needed, a cancellation will be announced by noon on Dec. 31.) The fireworks at sponsored by Hunter’s Shop ’n Save; Piscataqua Landscaping and Tree Service, and Black’s Paper Store and Gift Shop.

“Our partners, sponsors, volunteers, and supporters have helped make Last Night Wolfeboro a New Year’s Eve tradition,” says Linda Murray, chair of Wolfeboro’s Special Events Committee. “Support from hundreds of people across the Wolfeboro area have helped our team develop programming that provides positive exposure for our community and businesses,” she adds.

Brenda Jorett says, “In 2024 we had about 2,000 people attending. It is a very popular event, and we appreciate the donors that help fund Last Night Wolfeboro.”

All programming and updates about Last Night Wolfeboro will be posted on Facebook @LastNightWolfeboro and at Wolfeboro Parks and Recreation at www.wolfeboronh.us/672/Last-Night-Wolfeboro. Events are subject to change. Wolfeboro Community TV will offer a schedule of recorded concerts, shows, and special programming on New Year’s Eve. Last Night Wolfeboro presents free, family-friendly events (some events may have an admission charge.)

For those looking for a fun event to please holiday house guests and kids on vacation, head to Gunstock at 719 Cherry Valley Road in Gilford for a Torchlight Parade and Fireworks event on Dec. 28 from 4:30 to 7 pm.

When darkness falls, a serpentine formation of skiers and riders carrying torches will make their way down the mountain at Gunstock. (The history of ski torchlight parades dates back to the 1930s, and they have evolved from using actual flares to incorporating LED lights.)

A grand fireworks display will follow the torchlight parade. Gunstock’s Barrel Bar & Grille will be open for dining and drinks with live music leading up to the event. All are welcome to the celebration. Call 603-293-4341 or visit www.gunstock.com.

Many more New Year’s Eve events are happening around the Lakes Region; visit www.lakesregionchamber.org for listings.

If you love fireworks and the festivities that go along with them, Waterville Valley is the place to be on New Year’s Eve. Enjoy an Après Ski Party at the Freestyle Lounge (on the third floor of the Base Lodge) at 1 Ski Area Road in Waterville Valley. From 3 to 6 pm, Doug Thompson will perform.

Watch the sky light up when a dazzling array of fireworks is displayed over Corcoran Pond in Waterville Valley. The fireworks show starts at 7 pm sharp – don’t miss it! For event and other information, visit www.waterville.com.

What better way to end 2025 than a visit to the Gift of Lights at the NH Motor Speedway in Loudon? The family tradition of driving through approximately 2 1/2 miles of dazzling Christmas light displays at the Speedway continues this year with the Gift of Lights.

The annual event will have holiday cheer with about 3 million twinkly lights on display through January 4. Cruise the 2 ½ mile course past a dazzling array of sparkling lights and festive displays under the New Hampshire stars. Roll down the windows of your car, turn up your favorite holiday music, and make memories that will last a lifetime.

The Gift of Lights is open 4:30 to 10 pm on Fridays through Saturdays and Sundays to Thursdays from 4:30 to 9 pm. Holiday hours are Dec. 21 to 28 from 4:30 to 10 pm. (The Gift of Lights is a children’s charity event.)

For ticket information, visit www.nhms.com. The Speedway is located at 1122 Route 106 North in Loudon.

Make plans to attend the Lakeport Opera House festive New Year’s Eve Celebration on Dec. 31 from 7:30 pm to midnight. There will be music by the Eric Grant Band, dancing, and of course, a countdown to midnight. Get tickets at www.lakeportopera.com. The venue is located at 781 Union Avenue in Laconia.

Whatever events you choose, the last night of 2025 offers many ways to say a fond farewell to the year and to welcome in the new year of 2026, with more things to do and see in the Lakes Region.

A Festival of Holiday Trees and Plenty of Christmas Events

By Kathi Caldwell-Hopper

Christmas is all about the tree. Before the festivities get underway, the tree is a must. It is the icon of the season, with glittery lights, heartfelt and memory-making ornaments and always, a star or angel sitting at the tip-top.

The most well-known and beloved of tree displays is the Wolfeboro Festival of Trees, which takes place at the Wright Museum of World War II in Wolfeboro. This year’s event will be weekends from Dec. 6 to 14. The Festival is chock-full of fun events, along with the glittery, beautiful trees. A few of the special events are a Festival Craft Fair on Dec. 6 from 10 am to 4 pm, Pizza in the Pines, Santa Saturday and much more. Visit www.wolfeborofestivaloftrees.com for details.

Laconia celebrates the holiday season with glitter and fun events including tree lighting, a light festival and tree decorating. The series of events offers a chance for individuals, families, or businesses to sponsor a tree that will be set up and lit in Rotary and Stewart Parks in downtown Laconia by November 22. You can show your holiday spirit by decorating your tree with family, friends, or co-workers prior to the Holiday Parade on November 29.

From 9 am to 8 pm on Nov. 29, the public is invited to take a walk through the trees and watch the holiday parade, which begins at 5 pm. The trees will be lit at the end of the parade. For a complete list of holiday events in Laconia during Celebrate Laconia Lights Festival, visit www.celebratelaconia.org or email connect@celebratelaconia.org.

For a unique and memorable holiday experience, plan a trip to Castle in the Clouds in Moultonborough for the Christmas at the Castle event held on Nov. 22 and 23, Nov. 29 and 30, and Dec. 6 and 7 from 10 am to 4 pm. As you take a tour through the beautiful Castle, you will see Christmas trees aplenty. The rooms are decorated by local businesses, and each room has a definite style. After seeing the Castle decked out in holiday finery, head to the Carriage House, where an artisan fair offers wares by local vendors. You can bring the kids for photos with Santa and a chance to make a holiday craft and sip hot cocoa, and have cookies. The Carriage House Restaurant will be serving lunch, so no one goes away hungry! For information, call 603-476-5900 or visit www.castleintheclouds.org. The Castle is located at 455 Old Mountain Rd. in Moultonborough.

The 2025 Festival of Trees in Franklin is a project of the Franklin Opera House. The event will be held at the Franklin Public Library at 310 Central Street in Franklin and takes place on Dec. 5 from 4 to 8 pm, Dec. 6 from 10 am to 4 pm and Dec. 7 from 10 am to 3 pm. Donated trees by local families and businesses are on display, creating a beautiful sight. For information, call the Franklin Public Library at 603-934-2911 or the Opera House at 603-934-1901.

Trees and Trimmings will take place at the Remick Country Doctor Museum and Farm in Tamworth on Dec. 13 from 10 am to 2 pm. At the free event, you can sip on mulled cider and take a tour at the Museum Center, where each room will have a uniquely trimmed Christmas tree inspired by the exhibit space in which it’s located. Extra trimmings will include festive holiday touches, a make-and-take ornament station, and more. The Remick Museum is located at 58 Cleveland Hill Rd. in Tamworth. Call 603-323-7591.

In a beautiful and historic building in Bristol, a Festival of Trees will be offered on Nov. 28 from 4 to 8 pm and Nov. 29 from 10 am to 7 pm. The event will offer everyone a chance to enter a winter wonderland and see the decorated trees. You can also purchase raffle tickets to support the Newfound Performing Arts initiatives. The Historic Town Hall is located at 45 Summer St. in Bristol.

Along with the tree events, many other happenings will brighten the holiday all around the Lakes Region in the upcoming weeks.

The little town of Bristol in the Newfound Lake area is a favorite place for Santa, and he makes his annual visit each Christmas season. This is the 70th annual Santa’s Village at the Tapply Thompson Community Center in downtown Bristol. Santa will be on hand to greet kids on Friday, Dec. 12 from 6 - 8 pm. He also will be at the Center on Dec. 13 and 14 from 2 - 5 pm. The Community Center will be transformed into a magical holiday wonderland with Santa’s elves building toys and wrapping gifts. Attendees will be treated to one of Mrs. Claus’ delicious homemade cookies. Also at the event guests will have a chance to see the North Pole Train Station and lots more. Added to this, all families will get to spend time with Santa and receive a special commemorative ornament. The event is free, and all are welcome. Please bring a canned food donation.

Also at the Santa’s Village event will be the annual Christmas Craft Fair to benefit the Tapply Thompson Community Center. It is a chance to browse the craft tables in the Center and do some holiday shopping. Call 603-744-2713 for details.

There is nothing like an old-fashioned Christmas event, and the Remick Country Doctor Museum and Farm at 58 Cleveland Hill Rd. in Tamworth will offer, on Dec. 18 at 6:30 pm, the Pontine Theatre: A New England Christmas. The performance is sure to delight at the Remick Museum. Call 603-323-7591 or visit www.remickmuseum.org.

Santa and his elves will bring their annual Christmas Village to the Laconia Community Center at 306 Union Avenue in Laconia to offer kids a great way to spend a magical afternoon or evening. This is the 50th year of the fun holiday event scheduled for Dec. 4-7. Children can sample snacks, ride in a sleigh, join in fun games, and of course, see Santa to share their holiday gift list! Photos with Santa will be offered. Each child will also receive a gift. Admission to the event is free. Call 603-524-5046.

Plymouth will be bustling with activity during the holidays. The Hometown Holiday Celebration is scheduled for Dec. 6 from 4 to 7 pm on Main St. in Plymouth. The festive holiday parade takes place on Dec. 6; visit www.plymouthrotaryfoundation.org.

The Annual Holiday Concert will take place on December 6 at 2 pm at Plymouth State University’s Silver Center for the Arts in Plymouth. For tickets, call 603-535-ARTS.

Holiday music and entertainment will be offered at the Flying Monkey Movie House and Performance Center in Plymouth, beginning with Irish Christmas in America on Nov. 23; The Drifters’ Christmas on Dec. 5; Choir! Choir! Choir! on Dec. 6; and A Very Cher-y Christmas Tribute on Dec. 14. The Flying Monkey is located at 39 Main St. in downtown Plymouth. Call 603-536-2551 or visit www.flyingmonkeynh.com.

Light Up Night in Alton will take place on Dec. 6. The holiday tree will be lit in the Monument Square area of the downtown. Some of the events being planned are visits with Santa, craft projects for kids, music, and more. Visit www.altonbusinessassociation.com. Plans are underway; call Alton Parks and Recreation at 603-875-0109.

Mill Falls Marketplace in downtown Meredith is a magical shopper’s paradise at Christmas. On Dec. 7, the Mill Falls Marketplace Annual Holiday Open House runs from 1 to 4 pm, with performances by Rhythm of New Hampshire Choral Singers, reading from the Polar Express by Miss Karen, refreshments, and more…and of course, a chance to enter to win a $500 raffle! For information, visit www.millfalls.com or call 844-745-2931.

An 1860s Victorian Christmas on the Farm on December 6 from 10 am to 4 pm will offer a chance to travel back to a simpler time before there were cars and big machinery at the NH Farm Museum. Guides will be in period dress and ready to welcome guests as they arrive. The property will be decorated with freshly cut pine boughs, garlands, and wreaths. Make a pinecone decoration, meet young Emma Jones as she makes a gingerbread house, sing along, visit the tavern with a variety of craftsmen demonstrating their trades, and much more. The NH Farm Museum is located at 1305 White Mountain Highway in Milton. Visit www.nhfarmmuseum.org or call 603-652-7840.

The Lakes Region Symphony Orchestra will bring its holiday concert to music lovers on December 6 at the Colonial Theatre in Laconia at 7 pm. The second concert will be on December 7 at 3 pm at Inter-Lakes Auditorium in Meredith. The concert is called “North Pole Playlist” and will feature a mix of The Nutcracker, classic carols, and vocal hits with guest artist Taylor O’Donnell. There will also be a reading of Tomie dePaolo’s “The Legend of the Poinsettia” set to music. For ticket information, visit www.lrso.org.

Experience what life was like when candles lit the streets at the Gilford Candlelight Stroll on December 13 in Gilford village from starting at 5 pm. Dress warmly and stroll the streets to take in the evening lit with hundreds of candles. There will be horse-drawn wagon rides, hot cocoa, and holiday music. For information, call 603-524-6042.

The Colonial Theatre of Laconia brings some great holiday shows to the Lakes Region. On Nov. 29, Safe Haven Ballet will perform The Nutcracker at 4:30 pm. On Dec. 3, the beloved Vienna Boys Choir will take the stage at 7:30 pm. Dec. 4 offers Big Bad Voodoo Daddy: Wild & Swingin’ Holiday Party at 7:30 pm. The next holiday show will be the Lakes Region Symphony Orchestra with North Pole Playlist at 7 pm on Dec. 6. A Christmas Carol by Powerhouse Theatre Collaborative will run from Dec. 11 to 14. Dec. 19 brings Eileen Ivers Joyful Christmas, and Christmas With the Celts is offered on Dec. 23. The Colonial Theatre is located at 609 Main Street in Laconia. Visit www.coloniallaconia.com, or call 1-800-657-8774.

The Wolfeboro Friends of Music will present Lunasa in A Winter Solstice on Dec. 12 at 7 pm at the First Congregational Church of Wolfeboro. The show will bring “Ireland’s super group in an enlightened seasonal concert.” For tickets and information, visit www.wfriendsofmusic.org.

NH Veterans Home Ensures Residents Feel Welcome

Commandant Kimberly MacKay at the entrance of the NH Veterans Home in Tilton. (Tom Caldwell Photo)

By Thomas P. Caldwell

When military veterans find they need a more formal living arrangement due to medical and other personal needs, the New Hampshire Veterans Home in Tilton is often their first choice. The reason is clear: The home, established in 1890 as the Soldier’s Home for Civil War Veterans, offers not just an assortment of care options but also a welcoming setting that includes recreation and travel options.

With a large volunteer base expanding on-site activities and sponsoring trips to sporting and cultural events, the residents are able to pursue their interests to the extent of their physical limitations. There are trips to an apple orchard in October, bowling in the winter, movies at Smitty’s Cinema, and an annual trip to a Red Sox game.

The New Hampshire Veterans Home also preserves the residents’ military traditions, with ceremonies recognizing their achievements in the service and the holidays established in their honor.

“It’s very important to them,” said Public Information Officer Sarah Stanley. “Our Resident Council is made up by members of the veteran residents here, and they participate, from reading proclamations for the governor to opening prayers, to leading us in the Pledge of Allegiance. So they’re very much part of our ceremonies.”

The upcoming Veterans Day program is an example of such a ceremony. Governor Kelly Ayotte will be the keynote speaker at the event, taking place on November 11 at 11 a.m., reflecting the date and time of the armistice agreement between the Allied nations and Germany that ended World War I, signed at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month in 1918.

Sarah and NHVH Commandant Kimberly MacKay recalled Ayotte visiting the Veterans Home when she was running to be governor.

“She came in to speak to our veterans,” Sarah said, “and one of the residents was talking to her about how state contracts always have to go with the lowest bidder, ‘and don’t we deserve to have a higher caliber of a food contract?’ So she said, ‘You know, what? If I get to be governor, I’m going to buy you a steak dinner.’ And don’t you know, she came in and she sponsored a steak dinner for all of them, and they had so much fun. I mean, she sat down, she cut veterans’ steak for them, if they needed assistance cutting, and she said, ‘You know, I had so much fun, I want to do this annually.’’’

Sarah Stanley, NHVH Public Information Officer, displays a handmade quilt presented to Robert “Bobby” McKeen, US Army and Korean War Veteran. Volunteers of the Patriot Piecemakers Quilts of Valor group presented the gift of love and warmth to thank him for his service after having been touched by war. (Tom Caldwell Photo)

“They may not all be Republicans, but that didn’t matter,” Kim added. “At the end of the day, they were sitting at the table with the governor and having conversation and really enjoyed it. And her team came. … She’s very, very supportive of the residents and the veterans, and it’s just a really wonderful thing, and they appreciate it.”

There’s a lot that happens inter-generationally, as well, said Sarah.

The home sponsors a Trick or Treat time at Halloween, with children from the community coming in. “The veterans love seeing the little kids, so, depending on weather, we’re all out here and all through the halls, and give out candy,” Kim said. “They get to talk with the kids and the parents, and it really means a lot to them.

“We hosted this year a fishing derby for the Elks. The Elks needed a pond, and so they came and used our pond, and that was wonderful. The residents just love to see the kids. So it’s really, really special.”

Sarah said that even older students like to come to the home. The Southern New Hampshire University Color Guard has come to post the colors during some of the ceremonies.

Kim said there were 152 residents as of late October, with 142 men and 10 women. Most are Vietnam veterans, while six served in World War II and 27 in the Korean Conflict. Others served in other capacities, with the youngest being a Gulf War veteran. Those who served in the Army are the most numerous, with the Navy and Air Force represented with 38 and 28, respectively, along with 12 Marines. There also are Coast Guard and National Guard veterans at the home.

Kim explained the criteria for admission: “We only have veterans here. That can sometimes be a little tough, because married couples want to come, but, honestly, if you look at our stats here, our waiting list is 23 and we have 43 applications in process. So if we added the additional layer of having spouses here, that would be an even bigger wait list. So we focus solely on the veterans themselves.”

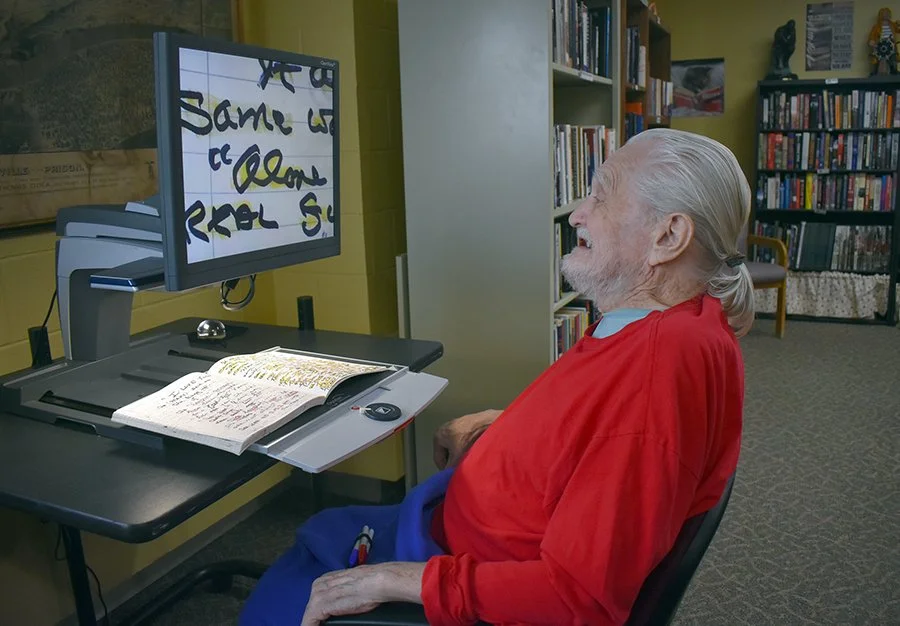

David Harris Jr., a US Navy Veteran, utilizes an enhanced vision magnifier in the NH Veterans Home Library to read the love story he wrote. (Tom Caldwell Photo)

Those admitted also must need physical care or help with daily living activities, such as reminders to take medications or help with food preparation. Some veterans have memory problems such that it is not safe for them to be at home any longer.

Leo, a member of the Resident Council, had nothing but praise for the facility. “It’s not an institution, it’s home,” he said. “Very welcoming. I mean, I could give you superlatives till you’re sick of them. … I tell people who I meet, who are thinking about coming here, that the issue is not going to be the way you’re going to be treated. The issue is your separation from wherever you are. You’re 80 years old, you’ve been independent all your life. You know you got to make a major decision at the end of your life. That’s what I tell them.”

Moving into the Veterans Home opens up new opportunities for participation with others or working to enhance artistic skills. Tom Gaumont has used his time at the home to experiment with watercolors and other media to create sketches and paintings, one of which hangs on a corridor wall.

Kim said the number of veterans is limited to how many they can provide the quality of care they need. With a general nursing shortage, the Veterans Home is attempting to increase its staff, but it wants to maintain a high ratio of nurses to patients.

“Medicare and the VA require a minimum of 2.5 hours of care for every resident a day,” Kim explained. “Five is a gold standard, and we like to stay in that four-plus range. We don’t ever want to be down in the 2.5-hour range.”

To meet the need for nursing staff, the New Hampshire Veterans Home has started its own LNA training program, teaching students to become licensed nursing assistants. It can boast a 100 percent graduation rate for passing the state nursing exam, having helped 50 students become LNAs. The home also provides advanced training for them to be able to pass some types of medications, giving them a path of advancement in the nursing field.

The range of care offered by the New Hampshire Veterans Home includes physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, dietary services, palliative and hospice care, and spiritual care. It has agreements with the Department of Veterans Affairs and local hospitals to provide inpatient hospitalization and specialized outpatient care.

Leo Leclerc, a US Air Force Vietnam Veteran, enjoys the comfort of his recliner while sharing thoughts about serving as the New Hampshire Veterans Home Resident Council 2nd Vice Chair. (Tom Caldwell Photo)

Even end-of-life care does not stop with a death.

“Veterans here do not pass alone,” Kim said. “We sit bedside, whether that’s the family sitting there, or if the family can’t be here or they need a break, we as staff will sit with them. We have volunteers that will come sit with them. We have a lot of pet therapy dogs that will come with their owners and the dog will sit with them at bedside.”

When people die at nursing homes, a funeral home picks up the body with no fanfare. Kim said, “Here, the residents have said, you’re our comrade. You came in the front door. You’re going to leave out the front door. … When a veteran passes, we do something called the final salute. They hold a ceremony, the residents come together. The family is there, the staff are there. They ring the bell six tolls. They read a little bit about the resident. They pass the mic and let people say things about that resident, and then they say a prayer and taps is played while the veteran is being moved through with the flag on them. And it is just the most incredible thing, if you haven’t seen veterans in their 80s and 90s standing at attention, saluting their comrades. It’s just incredibly moving.”

The home has a history of broadening its facilities and recently broke ground for an addition that will provide 20 new rooms, with the state paying 35 percent of the cost and the federal government paying the remaining 65 percent. It is a project first proposed in 2015 but did not reach the top of project list until 2023.

Kim said it will not add to the home’s residency capacity but is aimed at quality of life.

“We were approved for an addition to change some of our rooms where we have two people sharing, and the neighbor beside them has two people in that room, and all four of them share a bathroom,” she said. “We know that that’s not great quality of life, and we also know that that’s not good infection control. So we were able to go to the top, we got the funding, and so we are, right now, in the process of building a new neighborhood, which will be 20 private rooms with 20 private bathrooms. … So we can take some of those rooms that have two people in them and make it one, so now only two people are sharing a bathroom, versus four.”

Tom Gaumont took up artwork during the pandemic, and he continues to hone his skills after taking up residency at the NH Veterans Home. (Tom Caldwell Photo)

Through donations, they were able to install a walking trail to the pond that is accessible by wheelchair, and place gazebos, providing sitting areas for the residents. Some meet with families and have lunch while others just read and sit there quietly. Others walk the perimeter.

The Veterans Home also recently took ownership of a transit van that is wheelchair-accessible, along with a bus capable of carrying 12 people, allowing transportation to doctors’ appointments or field trips.

Inside, there is a “town hall” where entertainment and ceremonies take place, along with Bingo, Tai Chi, and chair yoga. Then, further down the “Main Street”, is a chapel with a full-time pastor, with other people coming in to provide additional religious services. There is a full library with large-print viewer and a “Vet Cave” with computers and stationery — as well as model train based on the Conway Scenic Railroad. To round out the experience, there is an occupational therapy gym, along with a store selling snacks, t-shirts, and other items.

For more information on the New Hampshire Veterans Home and the activities taking place there, see www.nh.gov/veterans or www.facebook.com/nhveteranshome.

A Gift to Veterans

The cover for ‘Orange’s Favorite Things’. (Courtesy photo)

By Kathi Caldwell-Hopper

We all need a magical journey now and then. For Jennifer Anderson of Moultonborough, the world around us is magical. She shares her happiness and all it encompasses with children in her first book called “Orange’s Favorite Things.”

If anyone had told Jennifer years ago, during the height of her career in the military, that she would fulfill a dream of writing a children’s book, she might have been skeptical.

However, that is just what she has done with her book launching in November titled “Orange’s Favorite Things.” The book is a gift to veterans, and Jennifer explains, “I will be partnering with K9’s for Warriors and donating a portion of my proceeds from the launch day to this amazing charity.”

The partnership is a wonderful gift to those benefitting from the K9’s for Warriors program. (Readers can order the book on November 11 - not before - with proceeds going for sales only on November 11.)

The book is geared for ages 3 to 8 and is centered around a cute little ball of energy, a girl named Orange. “She is patterned after me,” Jennifer says with a twinkle in her eye.

Jennifer has always been positive, energetic and enjoys adventure. She explains, “I grew up in Maryland with my parents and my sister. I have always wanted to fly since I was a child. My dad was a big history buff. He would take us to all the battlefields, air shows, and the Naval Academy. When we would visit the Naval Academy, he would say to me I would one day go there. I fell in love with the Navy and the idea of flying through my dad. He was drafted into the Army during Vietnam and did his initial time and got out.

“My dad was the inspiration for me attending the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. I attended from July 1991 and graduated in May 1995. I was a member of the proud class of 1995; we just celebrated our 30th reunion last weekend.”

Jennifer Anderson. (Courtesy photo)

That in itself would be a big accomplishment, but talking with Jennifer, it quickly becomes apparent that she does not let big obstacles get her down. Entering a field that was historically “male territory” never stopped her. (Much like the spunk and determination in the character of Orange.)

Jennifer’s military background is impressive. She explains, “I was a surface warfare officer first and completed my training in Newport, RI from September of 1995 until March 1996. I was assigned to the USS Wasp (LHD1) in Norfolk, VA. I was selected to transfer to the aviation community and started flight school in Pensacola, FL in October 1996. I completed flight training in 1998. (I was taught fixed wing and helicopter flight.)

“My follow-on was in HC-3 Packrats for initial h-46 Sea Knight training (North Island, CA) and I completed training in 1999. I was then assigned to my first 9 squadron, HC-11 Gunbearers (h-46 Sea knight (aka PHROG) in North Island, CA.”

She continues, “I was deployed twice as a Search and Rescue Helicopter pilot to the Middle East with the Gunbearers Det 4 on the USS Bon Homme Richard (BHR)(LHD6). The inaugural deployment for the BHR was in 2000 and again right after 9/11 in 2001 as a helicopter aircraft commander and XO of my det (det 4). We were one of the first on-scene in the Middle East after 9/11. Upon completion of my second deployment, I transferred to HMT303 (Marine Light Attack Training Squadron) located in Camp Pendleton, CA. I was a UH-1 Huey flight instructor for both Navy and Marine newly graduated flight school pilots.”

After her retirement, Jennifer (and her husband) moved to Moultonborough and Eleanor (Jennifer’s mother), relocated nearby. Jennifer and Eleanor are best buddies and share happy memories and stories. Perhaps it was growing up with a storytelling Mom that influenced Jennifer to write her book.

Jennifer says her mother always made up stories to tell her daughters. It created a world of magic for Jennifer, and she never forgot those childhood tales of children, animals and adventures. “My mother was truly the inspiration for the book,” Jennifer says.

Writing a children’s book is not an easy task, but Jennifer got help when she attended the Miriam Laundry Believe 2024 (September 2024) in Niagara at Lake Canada.

Jennifer Anderson and her mother. Jennifer’s new children’s book is set to launch in November. (Courtesy photo)

“It was an interactive experience to help develop the author mindset and a kickstart to creating. It was two days of speakers, coaching and workshops. Once I completed the conference, I started their publishing course in January of 2025 with about 20 other authors. We have monthly calls and an online course from the smallest kernel of a story to completion at the end of one year. My book will launch at the 11-month mark on November 11,” Jennifer says.

The character of Orange is a spunky, creative and vibrant child and her personality echoes that of Jennifer…and also her mother.

The story is about Orange’s favorite things, from feeding ducks and swimming with friends, filling the pages with delightful surprises and whimsical moments. Publicity for the book tells us that the book is “a heartwarming celebration of gratitude, joy and the little things that make life so magical.”

Another main character in the book is Orange’s dog, who accompanies the little girl on her adventures. “Everything in the book is taken from my life,” Jennifer explains. “It includes my parents and my sister, Heather. When I started writing the book last January, I knew I wanted it to be fun, joyful and colorful.”

Along with the fun of writing the book and it being a thank-you to her parents, Jennifer stresses, “I definitely want to give back to veterans.”

Every veteran will appreciate the message that encompasses little Orange: to have fun, not be negative but instead vibrant. “She is definitely a happy-go-lucky girl,” Jennifer adds. (One can see Orange’s personality on the book’s cover, illustrated by Amanda Porter.)

Along with writing her first children’s book, Jennifer also makes jewelry and is part of such organizations as the Moultonborough Women’s Club. She also spends a lot of time with her mother, traveling around the area and just having fun together. Additionally, Jennifer is an animal lover and says, “My mom told me many animal stories when I was growing up; we always loved to read books as well.”

All this is a world away from Jennifer’s life in the military, but she has not forgotten her fellow veterans. After the positive experience of writing her first book, Jennifer is now working on her second book. With a smile, she says she does not want to give out too much about the plot of the book. “Let’s just say it is about a squirrel!” she laughs.

The next book is sure to be as delightful as the first and will be awaited with anticipation by children (and adults) who love a good read into the magical journey of make-believe.

Discover information on where to order the book at ReadingwithGidget on Facebook and Reading_with_Gidget on Instagram.

The Good Old (Ghostly) Alton Town Hall

Alton Town Hall

By Kathi Caldwell-Hopper

Town halls across the state have served their communities well over the years. Those traveling around the Lakes Region will see many examples of the stately old buildings, usually two or three stories tall and made of sturdy brick.

Town halls are still used for a variety of purposes, and many were built to last in the 1800s to the early 1900s. The buildings are usually quite large, constructed of brick or mortar with three stories and in a Gothic design. They are used for, first and foremost, places where town offices, such as the town clerk, tax collector, selectmen, and other local government officials and employees, oversee the business of their town.

Over the years, as towns grew, the need for a place where speeches and plays and musicals could occur was needed. Churches were smaller and simpler in design, and there wasn’t much space for stages and seating for big groups of people. Thus, a section of a town hall was often set aside for public use.

These places were used for public gatherings, often with a large stage and plenty of seating. The town halls in some cases were renamed opera houses, and places like the Franklin Opera House in the area is a fine example of one such building.

Town halls can be imposing structures, and this time of year with Halloween looming on the calendar, they can seem spooky.

Spooky is one thing, but spine-chilling ghostly occurrences are quite another. The Alton Town Hall has a reputation for ghostly happenings and most people would rather not be in the building late at night – alone.

Originally built in 1894, at a cost of around $15,000, you cannot miss the Alton Town Hall, as it sits in the center of the village. Its design is in the Romanesque Revival style, with a brick exterior.

Perhaps the thing (other than a reputation for being haunted) that sets the building apart from more modest halls is the 85-foot tower with a Thomas E. Howard clock. One of the unique things about the hall is that it has clock hands that measure over three feet long on all four sides. If you needed to know the time, all you need do was gaze up at the tower and be informed.

Historically, the building housed the Fire and Police Departments on the lower levels with a jail cell in the basement. In the early days, there was also space set aside for the town’s library and a bank.

Like others, the Alton Town Hall was used as an entertainment and gathering place over the years, with a stage where concerts, local acting groups presenting plays, and even movies and graduation ceremonies took place in an auditorium.

Like all town halls, the building in Alton has long served the community. But it is the ghostly reputation that sets it apart and has gained attention even on television shows and in the news media. The things that have happened – and could still occur – are downright fearful in the old building. How can one explain such things as mysterious voices with not one person who could be talking or furniture moving around?

Just who is the ghost that does all these scary things? Some believe the haunting is done by the ghost of a strong outdoorsman but there may be others at the business of haunting as well.

To explain why groups of furniture have moved around, that woodsman was likely quite strong. Perhaps he had the strength to move furniture around and rearrange chairs when the building was unoccupied.

For a spine-tingling and downright unexplained happening, how about this one? Odd and creepy in the extreme, a local person was said to have heard furniture being moved in the space on the next floor. It was late at night, and the person was alone in the Town Hall. One can imagine they went to explore and see what all the noise was about when they assumed they were alone in the building.

What did they see? Outside the courtroom, the chairs were in the hallway, arranged in a single-file line. Could it be the old woodsman’s ghost, deciding to play a joke on the one living person in the Town Hall that day? Or some other explanation we may never know the answer to in this life.

In other cases, footsteps have been heard in the building when no one was around. This in itself would send anyone from the building – at a brisk pace!

One explanation of why multiple footsteps are heard in the old building is the fact that the space was once used as a school. That might be the reason for all the footsteps. Perhaps ghosts of the former pupils are locked in time in the place, searching for their classrooms and teachers from long ago? One report tells of a child – a little girl – dressed in outdated clothing – gazing down onto the street from a vantage point on an upper floor.

Another report tells of things happening in the Alton Town Hall’s basement. According to www.myluxvaca.com, the basement is not a place anyone would wish to be alone at night. It is said to be haunted by a janitor who died years ago. His spirit is said to lurk in the building and the basement where he might have had an office or stashed his cleaning supplies. (Perhaps he is the culprit of the furniture moving around?)

With such a strong reputation for hauntings and ghostly occurrences, it is no wonder the Alton Town Hall has been the subject of paranormal television shows. What did these ghost hunters discover in the building?

At the least, ghost hunter equipment has captured voices from another world while in the building.

Another tale is that a woman met her end in Alton and her figure is seen on the stairs, leaving a sense of sadness or uneasiness in that spot.

These days, the town hall continues to serve the community, and some people are skeptical of the ghosts said to linger there. The imposing clock tower remains and within the building, town business serves the community as it has done for years, with administrative offices, an office for the tax collector, town clerk and other government and town business.

It seems few people avoid the Alton Town Hall, with some being curious. But locals come and go, conducting business there as they have done for years.

Perhaps the woodsman and janitor and the former students, among others, look down upon the living, and talk among themselves about new pranks and scary things they might do to keep the legends alive at the Alton Town Hall.

Creating Ukrainian Pysanky Eggs

Ann Dutile at the Ladies of the Lake Fall Craft Fair in Laconia. (Kathi Caldwell-Hopper photo)

Story and photos by Kathi Caldwell-Hopper

Imaging traditions that date back 5,000 years is difficult. Old customs would seem faded into time, but one that remains is “decorating” Ukrainian Pysanky eggs.

Creating the intricate designs on real – not fake wooden or plastic – eggs is a practice that takes patience and is a learned skill. It is not just for Easter but a year-round art form that not many people are doing any longer or even know much about the Pysanky traditions.

Indeed, respecting traditions are a vital part of crafting the colors and designs used for Pysanky eggs. One such creative person is Belmont resident, Ann Dutile. Her work is breathtaking, and customers call it “amazing” and “intricate” when they visit her booth at artisan fairs. She has honed the crafting of Pysanky eggs over time, using practice and patience, two things that are vital to making the designs.

“I was introduced to Ukrainian egg decorating by my high school art teacher. That teacher was into it and when I saw the finished product, I fell in love with it,” says Ann.

That was the start of a lifelong love of making Pysanky eggs. “We would get together after school and my art teacher worked with me, showing me how to ‘write’ on eggs.”

Ann goes on to explain that decorating the eggs is called writing vs. painting. “It was an instant passion for me. Over the years, I would say I dabbled in it, but with children to raise and a busy life, there wasn’t always time to pursue it on a regular basis.”

Once Ann had retired and Covid hit, she found herself with more time on her hands and turned once again to creating Pysanky eggs. She says that by that time, with access to the internet and bigger art stores, the supplies were much easier to obtain. Thus, Ann was poised to dive into an art form that she loves and now shares with followers and new customers who may have never heard of Pankey eggs.

A variety of designs and colors in the Pysanky Eggs created by Ann Dutile. (Courtesy photo)

All one must do is come across Ann at an artisan fair (a list of her upcoming fall fairs is at the end of this story), and it is impossible not to stop and gaze at the eggs. People ask questions of Ann and are eager to learn more. Their amazement grows when they are told that Ann makes the designs and creates each egg herself and that they are standing before an artist who is carrying on a very old tradition with dedication and skill.

When asked why she chose this art form, Ann says it is because it is relaxing and “meditative.” One can see why she gets lost in each design as the everyday world with all its stresses and tasks falls away. “I enjoy thinking about the colors and designs I will make. It is relaxing and a form of meditation for me,” she explains.

To outline what these eggs are and how they are crafted, Ann says, “Ukrainian Eggs are hand drawn on real eggshells using a wax resist dye process. I draw on the eggshell with hot beeswax which comes out of a miniature brass funnel called a Kostka. The wax seals the color, and I work from color to color, often light to dark. When I’m finished, I melt the wax off against a candle flame and wipe the wax off with a tissue. The designs and colors are revealed.

She continues, “According to an old Ukrainian legend if pysanky (Ukrainian eggs) are being made, evil shall not prevail over the good in the world. Each symbol and color have meaning based on ancient traditions.

The symbols and colors are many and Ann mentions just a few, including birds representing fertility and fulfillment; butterflies the resurrection of Christ; deer and horses symbolizing wealth and prosperity; flowers for wisdom and elegance and beauty and poppies the most beloved flower in Ukraine (poppies often show up in designs.)

Colors can be, for example, red which symbolizes happiness and hope; white for purity; blue as the sky and good health, and orange for the sun. Ann says she uses these colors and weaves the design ideas into her work but goes beyond the traditional when she adds in further colors and creates her own designs.

And what about the eggs? To spend time and skill on the eggs, one would imagine Ann uses wooden eggs which would be durable, but that is not the case. Her egg choices come from local farms vs. the grocery store

A variety of designs and colors in the Pysanky Eggs created by Ann Dutile. (Courtesy photo)

“I use a variety of real eggs,” she explains. “I use chicken eggs and sometimes others such as turkey eggs or even goose eggs. Chicken eggs are good for doing details and designs. They take me, on average, about six to eight hours to complete and can be quite detailed. A goose egg might take me the same amount of time while other types of eggs require a different time frame.”

The process of making an egg requires Analine dyes, which Ann says come in many colors, from the traditional, often used hues to her choices of additional colors such as various pinks, for example.

Beeswax is the only type of wax Ann uses when making Pysanky eggs. “My creations are done with beeswax and dyes,” she says. What sounds like a simple, straightforward “craft” is anything but easy and quick. It requires the talent of creating a design, drawing it onto the egg and then utilizing beeswax and colored dyes.

Should one wonder if the egg retains its yolk and white innards, Ann reassures she removes them for the simple reason that she does not want any undesirable odor to come from the eggs. She carefully blows out the innards before beginning to “write” a Pysanky egg.

“Is there a big learning curve if you want to make a Pysanky egg?” Ann says she is often asked. “The answer is yes, and no. One of the challenges is learning to paint on a round surface. Also, there is no erasing when making a Pysanky egg. It takes patience and practice and once you start a design there is no turning back or erasing. I learned the process quite quickly within a week, but my designs back then were quite basic and simple.”

“Simple” is not a word used to describe the intricate designs Ann now creates. She is a true master of her craft, as witnessed by those who are lucky enough to see her work at a local fair. Customers buy the eggs for gifts, with the upcoming holidays a favorite time to gift a Pysanky egg, to those who collect the eggs for themselves. To own an Ann Dutile created Pysanky egg is the goal of many who love and appreciate this traditional art form. (The eggs look great as a holiday tree ornament.)

Customers and creative types who find themselves drawn to making Pysanky eggs can contact Ann, who says she has taught the craft before and is open to doing it again. Once a student makes a Pysanky egg, they will likely know what Ann means when she says the process is deeply meditative. It is also a respectful nod to the distant past, dating back 5,000 years.

See Ann’s Pysanky eggs for sale at upcoming fairs, including the Belmont High School Fair on November 8 from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. and the Gilford High School Holiday Craft Fair on December 6 from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. For information on taking a class or to learn more about an event where one might see the Pysanky eggs, email Ann at anniedutile@yahoo.com.

Sandwich Gallery Offers Unique ‘Local And Beyond’ Art

Larinda Meade is one of the featured artists at the Patricia Ladd Carega Gallery in Sandwich. (Tom Caldwell Photo)

By Thomas P. Caldwell

The Patricia Ladd Carega Gallery in Sandwich, which operates seasonally from Memorial Day to Columbus Day, reflects a commitment to showcasing unique art in all media, created by both emerging and established artists. While 80 percent of the artists have local connections, the reach is much farther, with the gallery’s roots stretching all the way to Paris, France.

Founder and owner Patricia Carega relates, “We were living in Paris, and I have a very good friend who opened a gallery there, and several nights before we were due to leave and come to Washington [DC], we had a little bit too much champagne, and she said, ‘Wouldn’t it be nice if you opened a gallery in Washington, an international city? Take some of my artists, and off you go.”

She took that advice and opened her first gallery in Washington in 1983, operating it for nearly a decade.

“I very quickly learned that Washington supports Washington DC artists,” she said. While patrons appreciated the international art, there was such a strong local art community that those artists were the ones people were most interested in seeing.

Economic concerns led to her closing the DC gallery in 1993, and she moved to Miami; but she also maintained a love for New England.

“I was born in Massachusetts, and I love New England,” she said. “My brother lived here … and so I was visiting my brother, and I said, ‘Well, if you find me a barn, I’ll go back in the gallery business.’ Well, the barn found me. I found the barn, and here we are.”

She moved to Sandwich and opened the gallery in 2002, using the contacts she still had around the world to create the original exhibits. As time went by, she found more artists from around the Lakes Region and beyond who were happy to have a place to showcase their talent.

Shani McLane is one of the featured artists at the Patricia Ladd Carega Gallery in Sandwich. (Tom Caldwell Photo)

The gallery’s eclectic collection of contemporary art includes painting, printmaking, sculpture, ceramics, and jewelry, displayed with an eye toward ensuring that the works on the walls are in harmony with each other. Patricia regularly changes the way they are exhibited to enliven the collection, and she is happy to discuss the exhibits with those who stop by.

Because the barn is unheated, the gallery only opens during the warmer months, but she is able to extend the start and end of the season if the weather permits. She presents bi-weekly exhibits during the summer, swapping out the featured art to showcase other works, and holds opening receptions to introduce the artists. When interviewed in late September, the gallery was featuring works by Shani McLane and Larinda Meade.

Shani describes her prints as “individual essays capturing my personal thoughts and influences at a particular time in my life.” She brings her Scandinavia heritage to bear on interpreting natural patterns, “representing the importance of the natural world and its ever-changing existence as we know it. … I am more drawn to the interpretation and simplification of the overlooked beauty around us.”

Larinda is a painter and printmaker who focuses on the landscapes of Maine and New England. She sketches and takes snapshots of what appeals to her as she walks, using them as the basis for her images and prints. Her background as a studio arts major at SUNY Potsdam has allowed her to create work that is exhibited nationally and internationally, and has been placed in both public and private collections.

The Patricia Ladd Carega Gallery also holds creative activities and talks to engage the community.

Patricia says she is not herself an artist, but she was inspired by living with an art-collecting family, and has an interest in art history. Her time spent in Italy, France, and the United Kingdom broadened her background and further shaped her appreciation for all types of art.

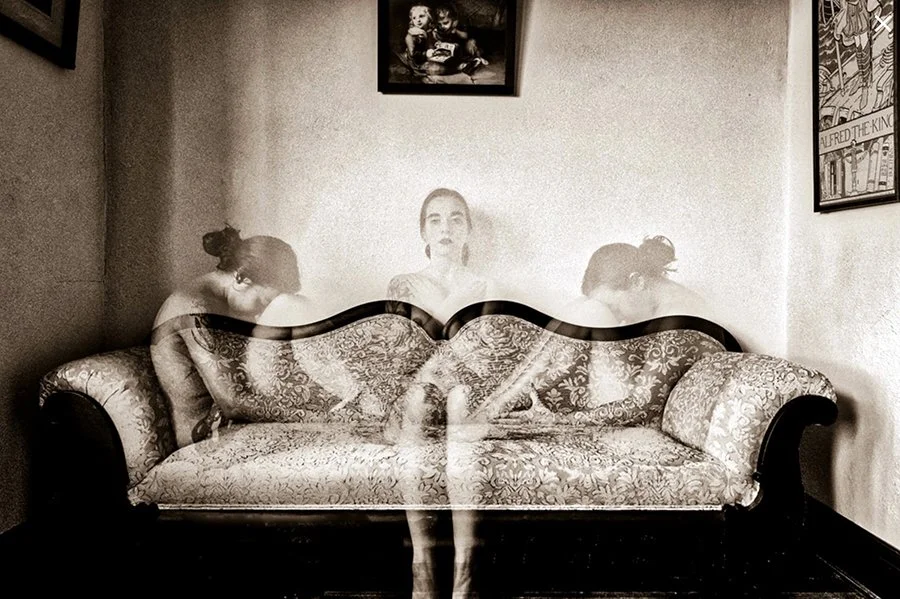

The Patricia Ladd Carega Gallery is the exclusive exhibitor of the photography of Brook Hedge of Sandwich. (Courtesy Photo)

Artists exhibiting at the gallery include Margery Thomas Mueller, who works with Yupo paper, a polypropylene sheet that can be difficult to control. “The moving ink and moving graphite speak to … emotions,” she has said. “Knowing that I can erase the entire picture plane with strokes of water and ammonia relates to what is happening in the human landscape as it transforms.” She starts with a basic composition and lets the medium lead her along.

Dayna Talbot is a multidisciplinary artist who works with fiber, paint, and sculpture to create a broad range of artistic pieces of both two and three dimensions. Her installations and sculptures are displayed alongside her paintings, prints, and handmade paper. “Ritual and repetition guide my creative process,” she said, “with colors serving as metaphors for purity, protection, and introspection.”

Pam Urda takes a whimsical approach to art, using found objects to create sculptures and tiles to create unusual shapes or beautiful globes — whatever strikes her fancy. “All I know for sure,” she says, “is that my art cracks me up on a daily basis and, in my opinion, that is a great way to live.”

Brook Hedge is a Sandwich photographer who spent 40 years in the legal profession in Washington, DC. She studied with a variety of professionals and, after exhibiting around the country, now uses the Patricia Ladd Carega Gallery as her exclusive venue.

One of the more unusual artists at the gallery is Dan Falby, who uses “meticulously worked clay slabs” to create hardened ceramics that retain fluid impressions from being dropped and tossed. “I use play, chance, and a collaboration with gravity to create ceramics that are a visceral record of movement and materials colliding,” he says. “I am drawn to how forms in nature tell the stories of their creation in the marks on their surfaces and the posture of their bodies. Erosion by wind and rain, freeze-thaw cycles, tectonic upheavals, and biological growth and decomposition create an intricate web of contingencies that shape our world. I strive to make sculptures that possess a similar elemental happenstance.”

The gallery has many more artists using various media to offer their unique visions.

The gallery is open Thursday - Saturday from 10 am to 5 pm and Sunday from 12:30 to 4 pm. Patricia planned to hold a season-closing party on Oct. 4 from 5 to 7 pm. Its last day open is set for Saturday, Oct. 11, although if the weather holds out, Patricia may extend the season.

Enjoying Gunstock Year Round

Construction work at Belknap Mountain Recreation Area (Gunstock). (Photo courtesy Gunstock)

By Kathi Caldwell-Hopper

If you want to go for a hike, take a Zipline, ride a chair lift to see the Lakes Region from on high, or enjoy skiing, there is just one place to do so: Gunstock Mountain Resort in Gilford.

The resort is beloved by many and has been around in one form or another since the early part of the 1900s. That is long time, with the area undergoing a bevy of changes over the years.

People first heard of skiing in the late 1800s, and in those days, it was a rudimentary sport. It began in Berlin, New Hampshire, where a group of Scandinavians were working on the railroad system. The work brought them to the northern part of the state, where there was deep snow and towering mountains, just right for a sport they had been doing in Europe for years: skiing. According to historical information at www.gunstock.com, Scandinavians made their own skis and created clubs for downhill and ski jumping. By 1882, skiing had become quite popular; thus, the Nansen Ski Club was established.

Not far away, Dartmouth College in Hanover brought outdoor recreation to the state with the Dartmouth Outing Club. By the 1930s, the club had promoted skiing to an extent to help it gain a foothold.

Famed European ski experts arrived during the 1930s, and skiers such as Hannes Schneider fled Nazi control to reestablish themselves in New Hampshire’s White Mountains. Their presence greatly helped skiing to grow in the state, and areas like North Conway became Meccas for the sport.

What was happening on the mountain in sleepy Gilford during this time? The answer is not a lot. Of course, everyone was aware of skiing, but most people had not tried it out. Early trails were cut by the Winnipesaukee Ski Club, which began as a group around 1915. Word got out about these trails and snow trains from Boston and points south stopped in Laconia, where enthusiasts could get off for skiing at the mountain in nearby Gilford.

Before Gunstock became an official ski area, Ted Cooke built a rope tow on the western hill/slope at Gunstock Mountain. The year was 1935, and Cooke did a good job with his tow, which turned out to be the longest in the country at the time. The idea of a tow to get people up a mountain when skiing seemed a godsend for those who wanted to pursue the sport. Thus, more tows were added at the Gilford slope.

An article in the Dec. 14, 1939 edition of the Bristol Enterprise titled “New Hampshire Winter Sports” related that Belknap Mountain Recreational Area in Gilford had added a 3,200 ft. chairlift on Mt. Rowe.

Construction work at Belknap Mountain Recreation Area (Gunstock). (Photo courtesy Gunstock)

Due to the popularity of ski jumping and the need for jobs during the Great Depression, Gunstock – or the Belknap Mountain Recreation Area as it was initially titled - was born in the 1930s. With Federal Emergency Relief Administration funds, a ski jump was built at Mt. Rowe in 1935. With foresight, officials sought more help to create a bustling year-round facility for all sorts of outdoor recreation.

To build such a place would require workers aplenty. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) stepped in and helped create the place we know today as Gunstock. Hussey Manufacturing Company, with offices in Maine, oversaw the workers, many who had been unemployed, thus boosting the local economy at a time (the Great Depression) when work was scarce. It would be the largest WPA-funded project in New Hampshire, putting many people to work.

Information at www.newenlgandskihistory.com relays that the initial plan for Gunstock was to make a $300,000 attraction to be called the Belknap Mountain Recreation Area. The plan was for a 60-meter ski jump, a slalom course, and two new ski trails. The plans were big; it was hoped the new area would bring the 1940 Winter Olympics to Gilford.

The official opening of the new area on Feb. 28, 1937 was a big deal. The kickoff event that followed was the United States Eastern Amateur Ski Association ski jumping event.

Chair lifts were soon added, which only increased Gunstock’s popularity. An article in the Dec. 14, 1939 edition of the Bristol Enterprise titled “New Hampshire Winter Sports” related that Belknap Mountain Recreational Area in Gilford had added a 3,200 ft. chairlift on Mt. Rowe.

The upgrades brought many skiers to the area. Old postcards and photos show a parking lot chock-full of cars with many skiers taking to the nearby slopes at Gunstock.

After World War II ended, people wanted to resume skiing, and some even hoped to ski during the summer months. In the summer of 1949, the Belknap Area tried something new: shaved ice and hay put down for a 40-meter jump in August! Thousands of people were intrigued and attended.

Every effort was made to create events in the area during the summer, with a campground added over time and some events.

One of the most significant summer events brought motorcycle races to the outdoor recreation spot. There was plenty of room at the Belknap Mountain Recreation Area, and a newcomer in a red hat saw the potential.

Frank (Fritzie) Baer was quite a character, wearing a signature red hat. He was a combination of shrewd businessman, manager, and a bit of a showman. Like many in his day, Baer worked hard from a young age, leaving school to work in a mill as a young man. Hard work never frightened Baer, and he put his energies into working for the Indian motorcycle company. He loved motorcycles and formed a club called Fritzie’s Roamers. He soon organized an event that kick-started Laconia’s Bike Week when he created a motorcycle rally at the Belknap Area.

The event was extremely popular as motorcycling was growing in interest. About 10,000 people attended the rally, which in part helped Baer secure the job as manager of the Belknap Area.

Baer was not a skier, but he likely saw the advantages of using the ski area for summer as well as wintertime sports and recreation. And why not when the area had acres of forests, a big parking area, camping, and slopes for winter sports?

Many events were held at Belknap Mountain Recreation Area, including, according to an advertisement in the July 31, 1958 issue of the Bristol Enterprise, an Antiques Fair held on site. Also in the same edition, mention was made that the Belknap County Fair was held at the Recreation Area from 1946 to 1949.

Over the years, managers came and went, bringing new things to attract visitors. T-bars were replaced with chair lifts, for example, and summertime campground improvements were added.

In 2011, a plan for more summer recreation at the area now known as Gunstock was unveiled, featuring an off-season plan that would cost upwards of $2 million. This plan included a treetop obstacle course, high-speed zip lines, and off-road Segway tours (in the autumn of 2011, the additions were completed).

Later, in 2016, a mountain coaster was installed on the lower slope of Mt. Rowe.

The years were up and down, with some seasons seeing a significant snowfall and others with sparse snow. The added expense of the off-season recreation also stretched the budget.

Despite the issues that can be common at most ski areas, Gunstock continues and is as vital a place, in summer as well as winter, as it has ever been. Summer offers a variety of activities, including the zip line, other attractions, numerous campground spaces, hiking, fishing, a Bike Week Hillclimb, a lodge with dining and live music, and events, among the activities.

The area that evolved into a grand destination was born with modest mountain slopes and a few intrepid ski enthusiasts. It has grown up to attract many who today arrive to enjoy Gunstock.

Making Connections with Lakes Center for the Arts

Local artist Larry Frates at a program by Lakes Center for the Arts. (Courtesy photo)

By Kathi Caldwell-Hopper

At Lakes Center for the Arts, it’s all about the artists and the community and connections. When the organization was formed in 2019 by a group of local artists committed to the world of art in all its beauty, they knew it would be a work-intensive task. They also knew that bringing more art into the Lakes Region and its communities would be worth the effort. “We knew we needed a central place to connect local artists to the community,” says Lakes Center for the Arts board member, Karen Jonash. She is a member and an artist, as well as a volunteer of the Lakes Center for the Art organization. Jonash speaks passionately of the mission of the Lakes Center and all it does for the area. “I was a high school art teacher for 17 years, so I know how important the arts are to connections and education,” Jonash explains. (Jonash is well known in the Meredith area as a sculptural ceramicist and a docent for the town’s Meredith Sculpture Walk. She is on the committee that selects the locations of various sculptures each year, which can be a challenge when there are up to 24 pieces to be placed.)

When it comes to art, Jonash says that in order for artists to stay in a community, they need a helpful place for support, networking and to show their artwork. The community can benefit from making, exploring and connecting when it comes to the arts. Art, Jonash says, even has health benefits. In 2020, when COVID hit not long after Lakes Center for the Arts was formed, the need for the arts was validated. While many people felt isolated during the lock-down, artists in the community could come together thanks to the work of the Lakes Center for the Arts. The organization offered – and still does offer - such things as rotating display cases around the Lakes Region where member artists show their work. Added to this, the organization’s website (www.lakescenterforarts.org) features an online gallery with examples of the work of member artists. Viewers are able to browse the pages of members and choose which artwork to purchase, or to simply bask in the wonderful work of the area’s artists.

Lakes Center for the Arts started from an idea of Katheryn Rolfe, who ran Oglethorpe Gallery, an arts gallery in Meredith. Rolfe was immersed in the world of art and was the person who originally pushed to create the Lakes Center for the Arts. She is still the driving force behind the group to this day.

The board of directors of Lakes Center for the Arts work tirelessly to bring the arts to those in the community. One way to showcase the work of artist members is with popular rotating display cases. “We have display cases in five locations around the area – Meredith Library, Wolfeboro Public Library, Castle in the Clouds, Laconia City Hall and Moultonborough Library,” explains Jonash. “We are looking to add to that list with more places to display.”

The cases allow Lakes Center artist members to exhibit their work for several months at a time, bringing them exposure and a chance to promote and sell their art. “We are trying to give local artists a chance to show their work.”

The Meredith Public Library has been very supportive of the Lakes Center for the Arts and hosts various activities such as workshops and presentations in their Maker Space.

Perhaps the best way to bring artists to the public is through the Meet the Artist program using space at the Meredith Library. Events are planned to inspire, educate and nurture the arts and connect the community through presentations, workshops and exhibits. All events are free and open to the public. Attendees can talk to the artist and ask questions about their work and art process.

Along with Meet the Artist events and the display cases, Lakes Center for the Arts also offers five varied programs and workshops each year. Each presentation is designed to offer a compelling experience for those who attend. The presentations have been popular, with a “Dress a Girl” group in April; Kathryn Field, a Meredith Sculpture Walk artist who presented a program to inspire others to pursue art, and Pai Louise Capaldi, an intuitive medium and artist who spoke about synesthesia. Upcoming programs include artist Bridget Powers on September 6 and on October 4, Robin Cornwell, noted fiber artist, will engage students in a tactile experience using quilting and printing on fabrics.

Artist members of the Lakes Center for the Arts all display a high level of craftsmanship, according to Jonash. While there is not a jury process to become an artist member, those who participate are skilled artists.

“We offer so much for artists in the Lakes Region,” Jonash goes on to say. “There is the opportunity to be on the website with a gallery of your work, to take a workshop, teach or simply to network.”

When it comes to artist networking, Jonash uses the example of Lakes Center for the Arts members helping one another determine pricing for artwork. Sometimes it is difficult to know what to charge for a piece of art and the input of fellow artists can be helpful. “We also try to strengthen the collaboration in the community,” Jonash says. To do so, it would be a dream come true for Lakes Center for the Arts to have a permanent home with a gallery and a meeting space. Presently the Center relies upon the generosity of such places as the Meredith Public Library to host art talks and programs. “They have been generous and so supportive,” Jonash adds. “We could not offer the things we do without them and others.”

For artists looking to connect with other creative people and the community at large, and to also find a place to display their work, joining Lakes Center for the Arts is a great idea.

The mission statement of Lakes Center for the Arts says it all: “Engaging artists and the community to inspire, educate, and nurture the arts.”

If art inspires and enriches everyone, the Lakes Center for the Arts is a good place to be. To learn more/become a member or get event information, visit www.lakescenterforarts.org.

It’s Apple Picking Time in the Lakes Region

By Kathi Caldwell-Hopper

“Surely the apple is the noblest of fruits.”

— Henry David Thoreau

Thoreau knew what he was talking about when he praised the humble apple. He probably reasoned what better food than an apple, which adds flavor unsurpassed as a snack or in a full-course meal?

Every year we look forward to the days when apples are ready for picking. Whether you love a good basic MacIntosh, or crunchy Paula Red or any other variety of apple, you know this time of year cannot be bettered.

This is the time of year when apple orchard owners open their orchards to an eager public to pick apples all over the Lakes Region and beyond. Farmers have been lovingly tending and watching their apple trees for months; apple producers say that in spite of a very hot, dry summer, the weather has not hurt the apple crops. Farmers report very solid crops this year with a large variety of apples from which to choose.

Apples are now ready for picking, and families can enjoy an afternoon spent at an orchard where not only apple picking is fun, but there are wagon rides to the orchards, live music, cider donuts, baked goods, and more.

A New Hampshire favorite orchard is Meadow Ledge Farm at 612 Route 129 in Loudon. Every year, Meadow Ledge has a huge variety of apples, and this year’s crop is proving to be a good one.

Meadow Ledge has about six dozen varieties of apples spread through a large orchard area, with the early season offering Jersey Macs, Blondies, and Zestars. Says Ernie, the owner of Meadow Ledge, “By mid-September we will have MacIntosh apples, which are a favorite with everyone. Following that are Cortland’s, Empire, Red and Golden Delicious and others.”

A number of varieties are available for pick-your-own, and most are also for sale in the country store on premises for customer convenience. Whether you want a full bag of your favorite apple variety or just a few to munch on for a snack, you are welcome at Meadow Ledge.

A fun day at Meadow Ledge Farm begins by grabbing one of the big red plastic containers for apple picking. Once the tractor arrives, hop on the flatbed for a fun ride to the orchard. Signs are posted throughout the orchard to let you know where your favorite apples are available for picking.

After your apple-picking adventure, hop back on the wagon for a ride to the country store. If you see eager customers placing their orders, you know you have arrived at the cider donut area. Watch while the Meadow Ledge crew makes your cider donuts right in front of you; enjoy them hot while you sit outside on a warm autumn afternoon.

The country store sells baked goods, including pies and breads, as well as candy, crafts, jams and jellies, dairy products, farm fresh eggs, honey, mums, and a lot more. Once apple picking season begins after Labor Day, the orchard is open seven days a week from 9 am to 6 pm until around mid to late October; after that, they are open up to the Christmas holiday season. Starting in January, the business is open on Saturdays with apples for sale until the spring season, when hours increase once again. Please call for information and definite hours at 603-798-5860 or visit www.meadowledgefarm.com.

Cardigan Mountain Orchard at 1540 Mount Cardigan Road in Alexandria is open with pick-your-own apples in a beautiful country setting. “We have many varieties of apples,” explains second-generation co-owner David Bleiler. The orchard spans many acres and is a definite favorite with those who like a scenic location with many pick-your-own varieties of apples.

The Bleiler family rejuvenated an old orchard in the 1970s and has been running Cardigan Mountain Orchard for over 50 years. They have updated, tended, and added to the orchard over the years.

The result is a wonderful place to visit, whether to pick your own apples or to stop by and purchase your favorite variety at the farmstand on the property. (You can pick apples in the orchard or stop by the farmstand for apples. Donuts, pie, and cider are available Thursday to Sunday while supplies last.)

Currently, as of press time, Cardigan Mountain Orchard was offering Paula Red apples with varieties such as MacIntosh, Cortland, Honeycrisp, and many more as the season progresses.

In nearby Bristol, the Cardigan Mountain Country Store, owned by the Bleilers, is located on Lake Street. The store is a charming and fun place to visit, offering handmade items by local artisans, including soaps, woodworking, pottery, photography, and many other items.

Cardigan Mountain Country Store is well-known and popular for its homemade apple pie for sale in the store, as well as baked goods. “By the end of September, we will also have cider,” says David.

Cardigan Mountain Country Store is open until Christmas Eve; for more information and open hours/apples being offered for picking, call 603-744-2248 or visit www.cardiganmtnorchard.com.

For tasty pick-your-own apples, visit Surowiec Farm at 53 Perley Hill Road in Sanbornton. The farm is open daily through Columbus Day from 9 am to 5 pm with pick-your-own Macintosh, Macoun, Empire, Cortland and Ginger Gold apples; apples are also available for sale in the farmstand. (Not all apples are available at the same time, with varieties offered throughout the season

Says owner Katie Surowiec, “We are open for apple picking. We started the first week of September with MacIntosh apples. The orchard is within walking distance of the farmstand, so it is all convenient. The farmstand has vegetables, beef, other meats, eggs and we sell donuts from our donut trailer on weekends. We also have bread for sale.”

This year’s crop, says Katie, is good with a large variety of apples. The hot weather has not hurt the orchard at Surowiec, and she anticipates a good picking season. Call 603-286-4069 for information and updates.

For old-fashioned, delicious apples, cider donuts, and some music, head to Smith Orchard at 184 Leavitt Road in Belmont. The orchard has pick your own Honeycrisp, Ginger Gold, Macintosh, Cortland, Macoun and Jona Gold, and Red and Yellow Delicious apples. In the farm stand, apples, jams, jellies, honey, and maple products and mixes such as apple crisp mix, are for sale.

Says owner Wendy Richter, “This year we have something new: the Appleseed Café, where we offer apple cider donuts and coffee, as well as apple smoothies. There will also be live music on three Sundays, with music the last two Sundays in September and the first Sunday in October.”

The orchard is open daily from 9 am to 5 pm through around Columbus Day. Call 603-387-8052, visit www.smithorchard.com or email: info@smithorchard.com.

Butternut Farm, located at 195 Meaderboro Road in Farmington, is very popular for strawberry and blueberry picking during the summer season, as well offering other fruits for customers to enjoy.

When apple-picking season arrives, visitors can enjoy pick-your-own in over 30 varieties. Ginger Gold and Zestar are apples offered for picking as the season gets underway, followed by many other varieties with an apple for every taste.

Apple pickers can walk to the orchard, or those with mobility issues can ride on a handy electric passenger golf cart. Everyone is welcome at Butternut Farm, which is open daily (closed Mondays) from 8 am to 4 pm. The farm closes for the season in October.

A farm representative says the crop is good this year with plenty of apples. Butternut also has a cider house, offering five alcoholic ciders, pre-canned, growlers and cider wines. For updates, call the farm info line at 603-335-4705.

For a welcoming, down-home atmosphere, stop by Stone Mountain Farm on Rt. 106 in Belmont. Co-owners Joe and Cindy Rolfe love to “talk apples,” and Joe says he will always answer the phone to give current conditions for apple picking.

“We are open for the season, and we have 50 varieties, including Macs, Cortland, Fuji, Zestar, Jonah Reds, Empire, Macoun, as well as some of the oldest varieties in the country. The old-fashioned apples include Shazaka, Akan and Rambo, which are unusual and great types.